Bash Bish Falls

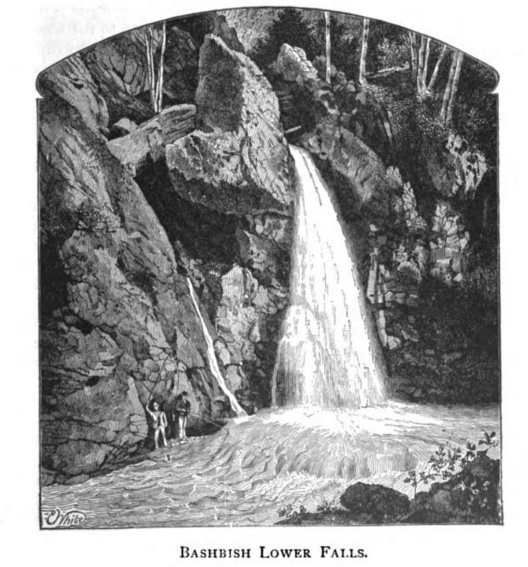

Hugging the border of New York and Massachusetts lies a raging cataract sequestered in a steep and rugged, yet sublimely beautiful ravine. The unusual titled Bash Bish Falls is Massachusetts highest waterfall, rising to 60 feet. Located in the extreme southwest of the state, it's easy for residents of New York to make a day trip, many of which, despite its presence in New England, classify it as a natural landmark of the Hudson Valley. For as long as records have been kept (and actually much longer than that) people have made pilgrimages to this spot to seek out and bask in the mighty and awe-inducing power of nature. There are conflicting reports of how this waterfall came to be named. Some say it's so-called due to a supposed Indian witch being executed at the spot, her name being Bash Bish. While the other, more believable explanation, derives, according to a 19th century author, "from an Indian onomatopoetic name," or in other words, garnering its name from the sound that falling water makes. In any case, it's certainly a unique name that most people are not likely to forget (with the exception of possibly reversing the order of the words). Before the colonization of the continent by Europeans, Native Americans undoubtedly visited the falls regularly, as these sites were believed to be the sacred abodes of spirits, a place to commune with the other side. The only direct evidence that exists which attests to their reverence of the place is a Mohican legend, if it is indeed genuine and not something crafted during the 19th century by romantic-style writers. The sad tale tells of multiple deaths occurring at the waterfall by supernatural forces (the story is appended at the end). When this sequestered spot become relatively accessible in the 1800's upon the introduction of the railroad, crowds of curious visitors would make the trip up from New York City to spend a day in the charming Taconic-Berkshire range. Numerous magazines and traveler's handbooks made mention of the area and, of course, the famous waterfall. "Bash-Bish... is one of the finest points of observation between New York and Montreal," the author of Health and Pleasure on "America's Greatest Railroad" stated in his passage of the falls, one of numerous natural features he detailed. The nearby station at the Copake Iron Works allowed passengers to disembark, walk up the winding road to the falls on foot, and be back in the metropolitan bustle of the city by nightfall. Despite the close proximity of the falls to the station, one guide book warned that "one requires a good foot, a strong hand, and a clear head" to those unaccustomed to the ruggedness of the area, which was significantly more extreme before the aid of modern roads and an improved trail system. Several publications also urged, or at the very least, described in vivid detail wild expeditions through parts of the upper ravine that park officials today would most likely discourage for safety concerns. One of the most sought after features was that of the "Eagle's Nest." This lofty viewpoint, a "blackened crag," towers "more than three hundred feet into the air" and "broods over the abyss." The journey up it was recorded as "perilous in the extreme" by one intrepid adventurer in the 1850's that also recalled that "scarce a foot-hold could be obtained, and we clung to the straggling plants in terror as we went." Despite the difficulty of reaching the spot, an unrivaled view emerged of the ravine and surrounding countryside. Standing on the edge of the precipice and looking down towards the falls, the people below resembled the miniature "Lilliputians of Gulliver's Travels."

"Profile Rock," a rock edifice resembling the face of a man, and the "Look-Off," another viewpoint of "high rocks on the south bank of the gorge," adjacent to the "Eagle's Nest" attracted additional visitors seeking an adventure. As excitement best describes the overhanging crags and ledges, so does beauty and "majestic loveliness" most aptly portray Bash Bish. Apart from the impressive height of the falls, what's really eye-catching about the scene is the titanic boulder that sits at the very edge of the cliff and diverts the flow of the raging brook. The water is divided as it tumbles over the edge, and then powerfully reunites into a single powerful stream again just before entering the swirling, emerald tinted plunge pool that "seethes and boils and bubbles like a great cauldron." Its elegance supersedes other waterfalls of the region. And like the unusual gap in the brook caused by the island-like boulder, the narrow ravine briefly disappears below the falls, expanding into a spacious glen—a fortuitous feature that enhances the scene and allows nature's remarkable handiwork to be adequately viewed. Crowds can gather in the natural amphitheater to simply take in the view, to photograph, and in years past to paint, all while enjoying ample space to freely move about. The heavy mist that exudes from the falling water is refreshing on a hot summer's day as it's gently blown this way and that by the fragrant mountain breezes that sweep down the ravine, similarly to the cool flowing water of the foaming brook.

Over the years, many have compared the beguiling intensity of the spot to the forces of magic. These "fairy falls" and surrounding countryside, endowed with Elysian qualities, seemed too surreal to simply house common arrays of wildlife, such as squirrels and deer. Rather, fanciful imaginations populated the region with supernatural entities, from phantoms of Indian myth to "fairy queens" that lived in "elfin palaces beneath the earth" imagined by 19th century romantics. Enraptured visitors were often at a loss of words. "I feel the paucity of description for delineating such scenery," one professor unabashedly admitted. Another "longed for the language of a poet" in attempt to express his elated emotion. And yet others felt the scene was practically indescribable. Not content that the present words of the English language would do it justice, one adventurer wished that "someone would invent a new vocabulary" for the purpose. And there were those who required no words to convey Bash Bish's grandeur. Painters flocked to the falls in substantial numbers throughout the 1800's. The Hudson River School artist John Frederick Kensett, produced perhaps the finest rendering in 1865. The painting shows a darkened glen, with summer storm clouds amassing overhead, adding yet another layer of wildness and intensity to the scene.

Other notable individuals who paid homage to Bash Bish consisted of the abolitionist and clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, along with the Transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and William Ellery Channing. "I would willingly make the journey once a month from New York to see it," Beecher wrote. While little documentation survives of Thoreau's visit, the prolific writer did make a brief mention of it in his work, A Yankee in Canada. This set of falls made an obvious impression on him; when he spoke of "interesting" waterfalls of the Northeast, he noted only two: Kaaterskill Falls and Bash Bish. The entire area surrounding the ravine is ideal "as a botanical hunting ground." Numerous uncommon to rare plant species are scattered along the brook and throughout the nearby forests. The combination of shade, dampness, and a variety of soil types has resulted in the presence of rare mosses, orchids, and other flowers. The unusual conditions of the mountain slope provide key habitat for species which would otherwise be absent in the more typical forest regimes of the region.

In May and June one traipsing through the "upper end of the gorge" may be fortunate enough to stumble upon small clusters of the wild blue clematis. This delicate flowering vine is often found in open light twisting around riparian trees or clinging to talus or rock ledges imbued with a hint of calcium. Orchids populate the shady forest interior, adding bursts of yellow, pink, and purple to the drab leaf litter of the understory. Before the introduction of a deadly exotic fungus in the early 1900's, impressive specimens of the American chestnut once graced the mountains here. "Chestnut formed a good percentage of the lower level growths and yearly yielded large crops until the disease made its appearance," Sereno Stetson wrote in the botanical publication, Torreya in 1913. "These beautiful trees," he continues, "two to three feet in diameter, are now decaying masses." While these mammoth and stately trees that provided tasty nuts to the area's people and wildlife alike no longer rise into the upper reaches of the canopy, traces of them can still be seen. Some roots from infected trees have survived, and it is not uncommon to see resprouts. However, as soon as they emerge above ground the fungus once again begins its insidious attack. Chestnut trees nowadays almost never achieve heights of more than 30 feet. While a majority of visitors seek out the mountains of western Massachusetts to see this popular set of cascades, it's important not to be overtaken by tunnel vision and miss out on the rest of the scenery. An "endless variety of attractions" await those who do even the most minor of exploring of the area's eclectic environs. Just be mindful of the rugged terrain while doing so. Along with being one of the most beautiful waterfalls of the Northeast, it's also one of the most deadly. Over 25 deaths have been recorded around Bash Bish during the last 100 years. Let's not add another ghost to the already crowded bunch. Although, I could think of places much worse to spend eternity than near this divine waterfall.

***

The Legend of Bash Bish

Deemed guilty of adultery, a young woman by the name of Bash Bish was condemned to die by members of her tribe. The Mohicans viewed this act as an unpardonable crime, despite the allowance of polygamy and divorce in their society. Because she was well-liked, and no one in her tribe could bear the thought of being personally responsible for causing her demise, it was determined to consign her fate to the forces of nature. Her unusual execution was to take place at the site of a large, rapidly flowing waterfall in the western Taconics. She was to be strapped into a canoe and sent to plunge over the falls, where she would undoubtedly be dashed to pieces on the sharp rocks below, afforded little protection from the thin-skinned birch bark canoe she was destined to ride in. At sunrise of the execution day, Bash Bish was tightly bound into the canoe, and only moments away from being launched into the foaming brook, when a dense fog quickly swept down the narrow ravine, obscuring everything. Out of view, Bash Bish somehow managed to undo her restraints and free herself. Knowing that she could never return to her friends or family, and finding the idea of having to start anew elsewhere absolutely repugnant, she decided to accept the punishment of death. However, it was to be done on her terms. Just as she clambered to the top of a massive boulder sitting at the edge of the precipice that divides the falls, the fog dissipated as quickly as it had arrived, and Bash Bish was once again in full public view. Everyone from her tribe was in attendance, gathered around the edge of the deep plunge pool at the base of the falls, including her infant daughter, White Swan. As she stood atop the crag silently gazing down at her people, a mass of butterflies, as numerous as the individuals congregated to watch her die, appeared seemingly from thin air and began to encircle her head like a crown. With every pass they picked up speed. What began as light fluttering quickly intensified into a frenzied swarm of activity. When the shocked onlookers half-expected a tornado to erupt from the ceaseless and turbulent rotation, Bash Bish leapt off the cliff, with the butterflies following her into the mist of the raging cataract. Though a long and thorough search of the plunge pool took place, her body was never recovered. Because of the sudden fog, prolific and strange behavior of the butterflies, and her vanishing without a trace, people began to suspect that Bash Bish was a witch. *** Despite her mother's tarnished reputation, White Swan managed to do quite well for herself. She had grown to become as lovely as mother had been. Upon reaching adulthood, she married the son of the tribe's chief. For years they lived in near perfect contentment. As time wore on, however, things took a turn for the worse when it became obvious that White Swan would never be able to bear her husband any children. Needing an heir to carry on his family's legacy, he was forced to take an additional wife. Overcome with sadness and needing an escape from the village, she began to take long walks into the wilderness. One day her aimless wandering brought her back to the fateful waterfall, a spot she hadn't visited since her days as an infant. Her relatives did all in their power to keep her away from the area, which since the odd occurrences of her mother's botched execution, was regarded with an equal mixture of awe and apprehension. That night as she lay in a deep sleep, her mind was overcome with a vivid dream of her mother beckoning for her to return to the site of the waterfall. In the morning she did as the dream commanded and visited the spot again. In her society, dreams were not to be dismissed; rather, they were thought to be divine revelations that were to be carefully analyzed and heeded. Day after day, White Swan sat along a boulder at the brim of the falls, dangerously close to the swift current, awaiting another message from Bash Bish, as the dream foretold would come to her at this very spot. Her husband worried with the depressed and fixated state of his wife—who he still loved with all his heart—did everything in his power to improve her spirits. Each day as she hovered at the edge of the cliff despondent, and mindlessly staring into the churning water below, he would bring her a new gift from the forest, a small token of his affection. On the tenth day, he came across a rare find. In a grove of cardinal flowers a pure white butterfly was alighted on one of the fiery blossoms. With the stealth that was natural to his race, he quickly crept up to the insect unnoticed and clutched it, imprisoning it in the hollow of his hands. Instantly, he set off to present his proud catch to White Swan. No sooner had he given the rare insect to her, she began to hear her mother's voice echoing from the plunge pool below. In a beautiful, intoxicating tone, Bash Bish urged her daughter to join her in the spirit world, where no worries or strife, she promised, could ever touch her. White Swan obeyed and stepping off the ledge, disappeared into the mist, the white butterfly trailing close behind. Her husband rushed to pull her back, but it was too late. In his eagerness to save her he had disregarded his own safety and, slipping on the slick, moss covered rocks, tumbled down the falls. As happened with her mother before her, no trace of White Swan was ever found. Her husband's badly battered and broken body, however, was cast up from the emerald-tinted pool and washed ashore. Visitors to the falls today, especially on drab, foggy days occasionally report encounters with the supernatural. Smiling faces are said to be seen in the foam of the plunge pool, while alluring, siren-like voices sometimes whisper from the spray of the tumbling water. A number of the numerous deaths that have occurred in the vicinity over the years have been attributed to these ghostly manifestations. Some say that they're the mischievous workings of an evil witch; others, that they're derived from melancholy spirits who dwell beneath the water, eager to acquire new companions to assuage their own loneliness. Either way, this curious waterfall is one best approached with a healthy dose of caution and trepidation.

The Hudson

The Hudson River has been described as an "arm of the sea." As a tidal estuary imbued with salt water and marine organisms that penetrate far inland from the Atlantic, this description is decidedly fitting. The Hudson is certainly one of the more unique water bodies in America. From New York City, the tidal portion of the estuary penetrates 153 miles inland where it abruptly ends at the Federal Dam in Troy. Along its lengthy career from the flat and sandy coastal plains of the Atlantic to the hilly interior of the Capital District that fringes upon the Berkshires and Adirondacks, the river is amazingly steadfast in direction, varying little in its north-south orientation, and essentially being as straight as an arrow, compared to the bulk of the country's other winding waterways. Traveling up it one encounters an unparalleled diversity of habitats and environments that often bewilders those making the trip for the first time. There's little wonder then that Henry Hudson thought this singular river might have been the fabled Northwest Passage leading to the Orient. The Hudson we know today began its life at the end of the last Ice Age. As a massive, miles-thick glacier advanced southward from Canada, the tremendous weight of the ice and accompanying debris it carried with it bulldozed and scraped the ancient landscape into its present configuration. Lofty mountains were planed and deep gorges were scoured in the bedrock. Over time, as the climate improved and temperatures steadily rose, the southern terminus of the ice sheet began to melt and slowly retreat, approximately 21,000 years ago. Flood waters from the ice streamed into the large basin that would become the Hudson. Tremendous amounts of glacial outwash (mostly sand and gravel) were carried by the powerful waters into the channel where they filled in the deep chasm, reducing its depth considerably. The steep and narrow passage through the Hudson Highlands, where precipitous mountains abruptly rise from the river's edge, is by far the most dramatic of the Hudson's scenery. This section is actually a fjord, similar to those of Norway and other Scandinavian countries. Despite having several hundred feet of gravelly sediment lining the bottom of the canyon-like fjord, the Highlands section is still significantly deep. At West Point, near a treacherous bend in the river's otherwise linear course, known as World's End, the bottom extends 175 feet below the surface of the water, and is the deepest spot of the river.

The Hudson Highlands are part of the ancient Appalachian Mountain Range, dating back to the Precambrian Era and contain rock a billion years old. The Appalachians were once higher than the towering Himalayas. Over the eons, the forces of erosion progressively wore them down to mere stumps of their former selves. This is the only instance in its 2,000 mile stretch where a river cuts through the mountain chain down to sea level. The Hudson experiences two high and two low tides per day that affect the entire estuarine portion of the river. If it wasn't for a dam spanning the Hudson in Troy, the river would continue its tidal action farther north. Above the dam the Hudson ceases to be an estuary. While the salt front doesn't penetrate as far as the tides, some marine organisms do make it all the way up to Troy. The tasty blue crabs are among them. The maximum extent of the salt front rarely ventures past Newburgh, although drought and high levels of precipitation will push it farther north or south, respectively. The greatest tidal range (the variation between average high and average low tides) occurs at Troy (around 5 feet), while the smallest range occurs at West Point (around 3 feet). Tidal flow in the Hudson is best described as water sloshing around in a bathtub. As one end goes up, the other goes down, with little variation happening in the middle. While both the lower and upper ends of the Hudson River experience extremes, in terms of water height, the Highlands and part of the Mid-Hudson are comparatively stable. Simply put, tides are driven by the gravitational pull of the sun, and to a much larger extent, the moon, along with the rotation of the planet. The alignment of these astronomical bodies determines the times and amplitude of the tides. Surrounding geographical features also dictate their strength and duration. In estuaries, tidal range increases as the basin becomes shallower and narrower. Tidal waves are forced to slow down as a result, thereby accentuating the tide. This is why Troy has the greatest tidal range—153 miles inland the river is exceedingly constricted and quite shallow compared to many other sections of the lower estuary.

Estuaries, generally speaking, are the most productive ecosystems on earth. A plethora of both marine and freshwater organisms cohabit an estuary's brackish (mixture of salt and fresh) water, leading to an exceptionally high diversity from a fusion of habitats. Moreover, estuaries are able to support such prodigious quantities of life by receiving nutrient-laden runoff from terrestrial environments. For marine organisms especially, estuaries are vitally important. Apart from containing richer water than the open ocean, these shallow and protected inlets offer a high degree of protection and abundant food for their offspring. While some marine creatures do not live here year round, they will return to spawn. Juveniles of innumerable species will thus start their lives in estuaries, such as the Hudson, and remain until adulthood before migrating to the ocean. Striped bass, American shad and other herrings (alewife, blueback), are but a few creatures that return to the Hudson at the start of spring to spawn. These types of fish are anadromous; whereas, the American eel, which spends most of its life in freshwater or estuaries, and returns to the sea to mate, is a catadromous species.

These migrants were an especially important food source to the native peoples that once inhabited the Hudson Valley. By use of nets and intricately designed traps called weirs, large numbers were easily captured. They would often mark their arrival by the blooming of the shadbush. The Hudson River Estuary has been known throughout history by a variety of names. From its current appellation, derived from the first recorded European to ever sail up it, the names descend into a dizzying array of titles. Called the Rio San Antonio, Rio de Montaigne (River of Mountains), Mauritius River, Great River, Orange River, North River, and finally Hudson River, this glacially scoured tidal basin has seen its name change nearly as frequently as the reversal of its tides. But perhaps the most significant sobriquet is its first, bestowed to the river by the Native Americans. They called it the Muhheakantuck, "the river that flows both ways."

1,000 Words

One of my favorite shots of this winter season is a scene of a thawing Hudson River, just as the very last rays of the sun slip behind a horizon filled with distant mountains and gently sloping hills dotted with historic riverside dwellings and bold architecture. Taken at Long Dock Park in Beacon, NY, one of the most heavily visited acquisitions of the environmental organization, Scenic Hudson, the site is one of the best spots to engage in Hudson River photography anywhere in the region. Apart from the stunning features of the park, visitors are allowed to remain past sunset, unlike most of the surrounding state parks that have strict policies that prohibit lingering for even a moment after dark. This generous laxity on the part of Scenic Hudson ensures the mesmerizing sunsets and idyllic twilight scenes are adequately captured. In the foreground of the image is the "dock" that lends the park its name. Upon acquiring the property, Scenic Hudson renovated the once derelict pier, transforming it into not only a work of art, imbued with wonderful symmetry and modern refinement, but giving it a more utilitarian use that harkens back to a time when the structure played a prominent role in the town's industrial past. Not visible in the image is a canal-like kayak launch that diagonally bisects the pier. The lights seen on the opposite shore of the Hudson belong to the town of New Windsor and the city of Newburgh. On the hill to the right, the one with the outline of tall buildings piercing the sky, George Washington was once stationed for over a year towards the end of the American Revolution. His headquarters were located on the brow of the once significantly less crowded hill. From here, he could gaze uninterruptedly to the soft shores of where I now stood and then peer beyond to the rugged Hudson Highlands at my back. Both the picturesque and sublime—a consummate and rare combination—often intermingle along these shores, and is what lent such inspiration to artists of the Hudson River School, a group that made capturing scenic landscapes a prominent and respected art form. The water of the estuarine Hudson is imbued with a silky texture from the moderate ice floes sweeping north as the tide rushes in. Taken during an early February thaw, most chunks of ice were little bigger than the size of a tire and were most densely clustered towards the pier and eastern shore. Dark, highly reflective ice-free zones can be seen toward the center of the river. A long exposure time resulted in a complete blur of the ice, giving it pleasing twilight hues that are brighter and more varied than the colors of the sky. The angular ice magnifies and scatters the light. Its charms are most set off when it emulates liquid and flows, yet possesses a greater luster and radiates richer and more vibrant qualities than typically drab liquid water. Longer exposures mix the two forms and seemingly create a new, unique state of matter.

Camera: Nikon D7200 Camera Settings: Mode: Manual Exposure/shutter speed: 15 seconds Aperture: f/16 ISO: 100 Format: RAW

To get the shot I used an 18-140 mm lens capped with a neutral density filter (Hoya NDX8) to reduce light intensity and ensure a total blurring of the ice without an overexposure of the image. On the pier I set up my tripod and began shooting in manual mode. I choose a standard aperture (f/16) and ISO (100) for landscapes. Due to the low light conditions and wanting to get the desired silky texture of the ice, I set the exposure time to 15 seconds (this would have been shorter if the sun was higher in the sky). And to allow for a fine degree of editing, I shot in RAW, which is my default setting. In Photoshop, I altered the colors somewhat to reduce the prevalent deep azures and pale yellows to a less clashing color scheme by tinting the photo purple, thereby providing more pastel hues. The various altered shades, ranging from crisp violet to soft lilac is more in tune with the ideals of a charming twilight scene. While natural sunsets with similar color regimens to the finished image do occur like this here, on the night of my photo shoot, intensely vivid colors were lacking. Photographers, like all types of artists, are given a fair degree of artistic license to create the scene as they wish it to be and not as it actually is—thus is art. Winter photography is often challenging. Dull monochromatic hues dominate a withered and subjugated landscape, with only the bare skeletal remains of the environment left to greet you. You are then therefore tasked to become creative. The team over at Light could be the solution to some of these challenges with their new camera technology. Its imaging engine allows for you to get beautifully-lit photos, even as the day's light begins to fade.

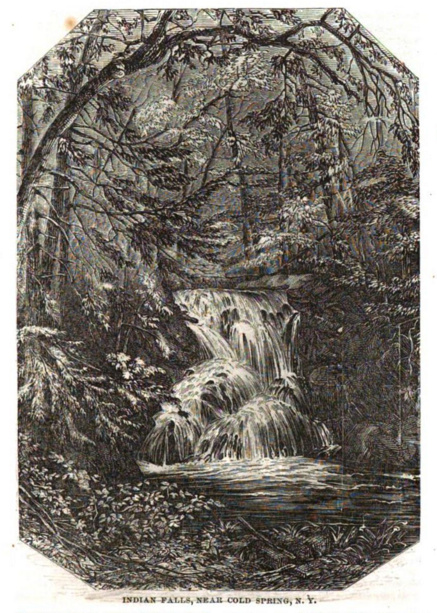

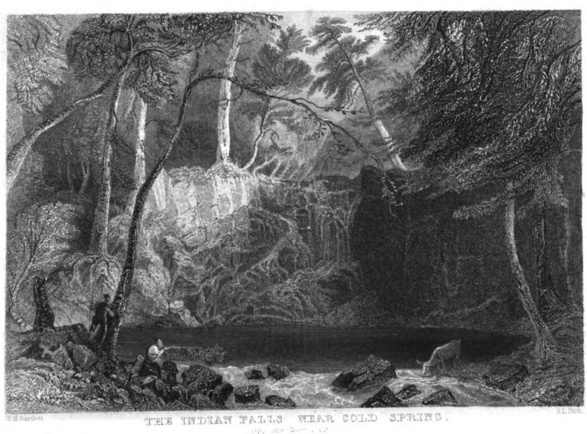

Indian Brook Falls

At the base of a deep and secluded ravine in the craggy confines of Putnam County, where the Hudson Highlands form an indomitable rolling wall of granite that makes even a short trip seem like a wild expedition, a small brook glides among jumbled boulders and the decaying trunks of hemlocks on its way to the Hudson River. About half a mile north of its terminus with the river, a sublimely beautiful 25 foot waterfall enlivens the tranquil, low-light surroundings. Indian Brook Falls has attracted countless visitors over the years, many of which, after glimpsing the wild grandeur of the spot, have been inspired to record the remarkable scene through paintings, verse, and prose (and now photography). Now residing on parkland, the falls are a protected treasure that will continue to offer its peaceful respite to all that require a momentary escape from the bustle of everyday life. Flowing into a marshy cove of the Hudson, known as Constitution Marsh, the area surrounding the outlet of Indian Brook was occupied for thousands of years by Native Americans, who had a minor settlement in the vicinity. Waterfalls were sacred places to most native peoples, believing these spots were the abodes of spirits. It is therefore unquestionable that these Wappinger Indians, a subtribe of the more encompassing Lenape, regularly journeyed to the falls to pray and conduct other religious ceremonies. The falls were once simply known as "Indian Falls," but the name was later changed during the 20th Century to "Indian Brook Falls," probably to help distinguish it from the myriads of others bearing identical names across the country. Throughout the 1800's, numerous descriptions of the waterfall and associated treks out to it were published in both books and magazines. These writings reached a zenith during the Romantic era, a period in which emphasis was placed on aesthetic experiences derived most notably from the raw and sublime forces of nature. The writings are prolifically descriptive and vivid, eliciting the same level emotion that a mesmerizing photograph today provides. High profile writer-adventurers, such as Nathaniel Parker Willis and Benson J. Lossing, were among those that helped catapult the site to fame. The noted essayist and author, Nathaniel Parker Willis, provides a singular description of the falls in his classic book, American Scenery, published in 1840. In his opening lines he calls Indian Brook Falls "a delicious bit of nature... possessing a refinement and an elegance in its wildness which would almost give one the idea that it was an object of beauty in some royal park." Further in his narrative, he documents an excursion out to the falls with a group of local residents aboard a wagon fashioned in the old Dutch style. To view the waterfall required travel on a rugged, and as he would later discover, dangerous road. The road was "in some places, scarce fit for a bridle-path," and so clogged with imposing rocks "which we believed passable when we had surged over [them]—not before." Eventually, a wide and level section of the road appeared; the driver then became “ambitious" enough to push the horses into a gallop, but being "ill-matched" in strength they jostled the fragile wagon in such a way as to detach several important features that sent the passengers flying to the floor. The mayhem was put to an end at a sharp turn in the road where the uncontrollable horses "unable to turn, had leaped a low stone wall." After salvaging one unbroken champagne bottle from "the wreck," the mostly uninjured party continued to the falls on foot and enjoyed a pleasant afternoon there.

The area not surprisingly became "a favorite subject with artists." Numerous paintings and engravings exist from the 19th Century that render the locale in near perfect likeness, and served as a simple photograph would do today in a newspaper or feature article. Others, however, show more free rein by the artist, boasting exaggerated features that are in tune with the particular inclinations and feelings of the era. The various depictions are useful for peering into the minds of the past and being able to witness firsthand the impressions the location made on these first intrepid nature seekers.

Another valued feature of the spot was its ability to act as a panacea, or restorative, to both the mind and body. "Tourists are always in raptures with the Falls," the editor of Dollar Monthly Magazine wrote in 1864, "because the sound of the moving waters is pleasing to the senses, soothing those who have tender nerves, and creating a feeling of delicious happiness." In a similar vein, another advocate of the potential healing powers of Indian Brook rapturously exulted, "May the heart, the spirits, the soul be here refreshed and refined!" Clearly, just as the Indians before them, the early residents of the Hudson Valley viewed powerful sites like these in a sacred manner. The unspoiled surroundings resembled to them an Eden, and they appropriated their time there accordingly. At the base of the plunging falls is a deep, expansive basin filled with transparent water and edged with a soft gravelly bottom, appropriately named the Musidora Pool (translated to "Gift of the Muses"), which according to Willis, "Nature has formed it for a bath." One has to wonder how many visitors over the years have cleansed themselves in the crisp water of the pool, similarly to the ablutions of a baptismal font.

The latter ghost was said to be the mastiff of Captain Kidd. A somewhat outrageous legend claims that Kidd burnt his ship in the vicinity around West Point to avoid capture by authorities. And by rowboat, he brought a portion of his secreted treasure to the mouth of Indian Brook where he promptly buried it. Before covering it up, he killed his dog and placed the body atop the pile of gold, so that the creature would guard it until his return. He never did make it back, though, having later been seized in Boston, transported to England for trial, and finally hung for piracy in 1701. As crazy as it might seem to have the infamous Captain Kidd sailing through the Hudson Highlands, he did have roots in the area. He made his home in New York City and had legal privateering expeditions financed by his associate Robert Livingston. It was said that he and his crew were sailing for Livingston Manor in the upper Hudson Valley the night the ship was lost. Numerous other legends abound as to the supposed location of his loot. Some say his ship sunk at the base of Dunderberg Mountain across from Peekskill and most of his gold still lies beneath the waters of the Hudson. Others attest it's hidden on the precipitous slopes of Crow's Nest Mountain behind a massive, unwieldy boulder called "Kidd's Plug Rock." And an even more unlikely tale tells of him transporting it west to the Shawangunk Mountains, where it was hidden in a remote cave among impenetrable pitch pine barrens. An 1880 editorial in the Putnam County Recorder claimed that "the dog's haunts are around the bridge that spans the chasm, just below the falls, sometimes being seen on one side, sometimes on the other." It further goes on to mention that one night as a carriage approached the haunted area at around "ten o'clock with six persons" aboard, a member of the party jokingly said, "'Now let us look for the dog.'" Almost immediately after uttering those fateful words a wild looking mastiff materialized alongside the wagon and began to make menacing gestures. The driver having a gun on his person, pulled it out and fired six shots into the beast. The bullets had absolutely no effect, and the phantom dog held his ground until the terrified group had quickly proceeded on their way.

***

*** Legend of “Indian Brook Falls”

Legend has it that during Henry Hudson's 1609 expedition, the Half Moon anchored one day near the mouth of Fishkill Creek. On a foray into the countryside, the crew stumbled upon clusters of wild grapes which they eagerly began collecting, hungry for anything other than a mouthful of stale sea rations. Intent upon the task at hand, they were unaware a group of Indians had arrived and surrounded them. Eventually, a crew member happened to notice something moving in the nearby bushes and walked over to investigate, at which time a volley of arrows were launched at the intruders. Having left a majority of their weapons back on the ship, there was little to be done except retreat. During the brief skirmish, the Dutchman Jacobus Van Horen was struck by an arrow and promptly captured. Assuming their compatriot was dead, the Europeans sailed on, never to return to so hostile a spot. Jacobus was transported south and presented to the sachem of the tribe. Intrigued by this strange white man, the first he had ever seen, he instructed his people to properly care for the prisoner. Over time, Jacobus was able to gain their trust, and was incorporated into the tribe. Meanwhile, the sachem's daughter, Manteo, quickly become enamored with the Dutchman and eventually asked her father permission to marry him. He happily agreed to the request and a wedding was set for the following summer. Over the following months Manteo and Jacobus would often meet at a secluded waterfall, sacred to her people, at the bottom of a deep and shaded ravine. Sitting beside the cascading waters that in little distance poured into a marshy cove of the Hudson, Manteo would muse with her lover about their upcoming nuptials and future together. Jacobus smiled and reciprocated the kind words, but inwardly he deeply missed his homeland and secretly prayed for deliverance. One spring day his prayers were answered. While out on a hunting trip, the deafening report of a gun noisily echoed through the still woodlands. Jacobus in an instant dropped everything and ran towards the direction of the shot. He eventually came to the shores of the Hudson, and spotted only a few hundred yards away an anchored ship flying a Dutch flag. Jumping into the water without the least hesitation, he swiftly swam up to the vessel and was taken aboard. And from there he disappeared. Manteo was heartbroken with this sudden departure, receiving not so much as a good-bye from the one she thought deeply loved her. Not long after, she too, disappeared. A few days later her body was discovered at the base of the waterfall she had spent so much pleasant time beside with Jacobus. Grieved beyond all consolation, it appeared she had taken her own life.

Emerson & Thoreau's Nature

"Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?" Ralph Waldo Emerson penned in the opening lines of his landmark essay, Nature. In it, the father of transcendentalism laments the fact that so many of us blindly follow the path of others, relying little on our own experience because we feel it is unnecessary or impossible to adequately obtain. Instead, he argues, that we should forge a "religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs." Essentially, he's saying that the prophets of the past should not hold an exclusive monopoly on pivotal adventure and insight; and that we cannot not solely rely on the judgment of these lucky sages, while disregarding our own. Transcendentalism stressed that each individual uncover their own truths by spending time in the heart of nature. By doing so, it's indeed possible to enjoy an "original relation to the universe," and extract wisdom more personally valuable than what we find in even the most revered passages of sacred texts or the utterances of our elders. Nature is living religion where we get to imbibe straight from the Source. Emerson was amazed how nature possesses the singular ability "to deify us with a few and cheap elements." Crimson rays of light, thin evening clouds, freshly budded trees, and crisp evening air might not amount to much individually, but pieced together naturally in the landscape and they form a moving and inspirational scene that teaches us about the nature of beauty, if nothing else. And beauty, Emerson was convinced, equated directly to truth. "Truth, and goodness, and beauty, are but different faces of the same All." By knowing nature and appreciating its many forms, figures, and arrays of varied color, it's possible to directly glimpse the face of the "Universal Being" and have its currents circulate through us. This is our revelation, our understanding of life's questions, and will serve a better guide than any second-hand account that hasn't been tailored to us. The landscape is more valuable for the impressions it makes upon the mind than by the quantity of natural resources it contains.

When we destroy nature, we deface the artwork placed before us. Will the torn and smudged scene ever make the same impression as before? When we lose nature, we lose beauty, and hence a portion of its refined essences, as morality and virtue, and all other positive attributes that inevitably derive from it. "All things are moral... shall hint or thunder to man the laws of right and wrong," Emerson preached, continuing, "this ethical character so penetrates the bone and marrow of nature, as to seem the end of which it was made." While we find peace and solitude and a respite from all noxious worries in the woods, and seem to think it akin to the feeling bestowed to us from a good night's sleep or calming medication, it in fact soothes not so much from us resting, as from stimulating that which has been slumbering in an unhealthy torpor for too lengthy a time. Moreover, nature offers commodities of more importance than the base-ic necessities of a more tangible nature, such as lumber, ore, or crops. Our language and habits of speech are closely related to our natural surroundings, and invariably so are our thoughts. We most frequently speak in analogies tied to elemental forms. "Light for knowledge" and "heat for love" are but a couple analogies of common vernacular that show how we prescribe natural elements to human thought. Their directness and simplicity are understood by all. But when we begin to use language for "secondary desires," selfishly applying words or phrases that show the significance and splendor of nature to hollow goals or strivings in order to increase our standing in some way, society as a whole takes a loss, as these words lose all their potency and fall flat, and in turn, nature becomes valued less, cheapened by attachment to vain longings, as riches, power, or praise. Emerson was sure that the "corruption of man is followed by the corruption of language," for as he observed "a man's power to connect his thought with the proper symbol, and so to utter it, depends on the simplicity of his character, that is, upon his love of truth." The poet in his estimation was the foremost of men. Poetry is language in its purest format and those who truly and dutifully ascribe words in such a way share a kindred relation to the influences of the natural world. Art is an imitation of nature and even a minor look throughout the artificial world we've created forcefully demonstrates the level of thirst we possess for it. Art thoroughly surrounds us, just as the forests and the vast sky arching overhead does. "'A gothic church,' said Coleridge, 'is a petrified religion.'" Analogy runs deeper than speech; it inspires and excites passionate action. We seek to bring nature closer to ourselves. These creations keep us attached to it even when far removed from the fields and forests.

*** With all of this philosophy in mind, Henry David Thoreau, the promising pupil and adherent of Emerson, also cultivated ideals thoroughly suffused with a nature-centric dogma. He similarly, and perhaps even more staunchly, believed in the value of the individual forging a life built atop the foundations of personal experience, rather than tradition. In his most prominent work, Walden, he insists "No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof." Thoreau informed his readers that instead of living through the eyes of others, it was possible to saunter into the "Holy Land" simply by taking a walk outside and roaming through the wilderness. Unlike Europe which had long ago exhausted its soils and littered the landscape with dwellings, the U.S. in comparison was a vast oasis of original splendor. This open and pristine country was equivalent to what existed in Europe hundreds to thousands of years ago, before the "foundations of castles" were laid, "famous bridges" created, and heroic fables told. Thoreau viewed Americans as being extremely fortunate in having a new template to work upon and learn from. To him, modern times were "the Heroic Ages itself" in which contemporary society was forging tales that would probably someday be revered the same as those from the past which are now commonly held in esteem. Most people have difficulty in perceiving this because "the hero is commonly the simplest and obscurest of men." In short, the quantity of open and unaltered space we possess, is proportional to the amount of unique experiences we can have. By preserving nature—saving expansive mountain tops and cramped valley hollows, thick verdant forests and slow moving rivers, the playground of the universe is also preserved, providing us with unending opportunities and delights. And what of our rapidly shrinking world? With land being heedlessly sold, subdivided, and with what Thoreau described as "walking over the surface of God's earth" being "construed to mean trespassing," how are we to get the most out of what currently remains in more developed areas?—simply view the landscape from afar. This, too, will satisfy many desires and similarly move and impress. The view of the whole, the larger picture, is ultimately of more worth. To this, men's "warranty-deeds give no title." The abstractness of the scene, far from solid and dictating, allows us to obtain what we ourselves determine to be valuable from it (i.e. the higher secreted qualities). But according to both Emerson and Thoreau, only those who have a keener and more subtle vision than the rest, "can integrate all the parts" and thus, unlock the items of value. Such vision, that which allows the sun not merely to illuminate the eye, but also "shine into the heart" belongs to those who understand the true purpose and nature of Nature, the poetically minded.

Thoreau elegantly put it like this: "I have frequently seen a poet withdraw, having enjoyed the most valuable part of a farm, while the crusty farmer supposed that he had got a few wild apples only. Why, the owner does not know it for many years when a poet has put his farm in rhyme, the most admirable kind of invisible fence, has fairly impounded it, milked it, skimmed it, and got all the cream, and left the farmer only the skimmed milk." Individual components are only as important as the level in which they blend into the landscape in a harmonizing way, as individual letters help form coherent words that give rise to sentences. The inseparable unions of rhythm and order, beauty and truth, only arise when we combine and expand our perceptions on a universal scale, and not, rather, constrict them to the microscopic view of what's directly before our eyes. Emerson concisely sums it up: "In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds some[thing] as beautiful as his own nature."

|