The Seven Wells (Dover Plains)

Manitou Well On the eastern flank of West Mountain in Dover Plains lies a series of “wells” or cylindrical basins that are carved deep into the bedrock along a steep-sloped brook. The deepest among the lot of seven plunges approximately 60 feet into the earth and is about half as wide. Each well is separated from one another by long fissure-like flumes. In some instances, the brook is narrowed to no more than a few feet wide, yet, in at least one spot, extends 30 feet down. The entire brook has a strong serpentine course. Its walls, polished smooth and containing unique striations that flare out wherever the walls are strongly curved, imbues the watercourse with whimsy. Waterfalls add to the scene. At the head of several of the wells the stream plunges perpendicularly, creating picturesque cascades and cataracts that make Seven Wells Brook one of the most beautiful streams in the entire Hudson Valley. The birth of the Seven Wells occurred around 15,000 years ago, at the wane of the last Ice Age. Its genesis is owed to the power of glacial action. As the mile thick Laurentide Ice Sheet began to recede north, it now, instead of bulldozing the landscape, began to alter it in other ways. The glacier melted especially unevenly against the sides of mountains and hills. At these uneven glacial fringes torrents of meltwater were channeled in certain areas. It’s important to note that the glacier, at this time, was in a pretty sad state, dirty and pitted. It was vaguely reminiscent of what’s seen in parking lots towards the start of spring, as once-massive piles of snow begin to reveal their hidden contents. In its heyday the ice sheet bulldozed anything it encountered on its march south, and in doing so acquired a substantial amount of debris ranging from pebbles to car- and house-sized boulders, all of which became trapped within the enlarging glacier. When it finally began to melt, the debris was condensed, some of which eventually exited the shirking mass via the torrents of meltwater previously mentioned. This slurry of liquid sandpaper cut through solid rock like a knife though butter. In the case of the Seven Wells Brook, the meltwater from a glacial stream followed a preexisting crack or joint in the bedrock, hence the narrow and deep course of the present brook. The crack was a point of weakness in the mountain and ensured the stream would cut more vertically than laterally. This is similar to how the nearby Stone Church was created. The wells were formed by powerful eddies within the stream. Gyrating stones caught in vortices of water drilled into the stone, ultimately creating the seven “glacial potholes.” Potholes such as these are sometimes referred to as a giant’s kettle or cauldron. The Seven Wells are among the largest glacial potholes in the Northeast, if not the country. The only comparable formation in the region is located in New Hampshire along the Lost River. Both the Seven Wells and the Stone Church (a spacious cavern in the mountainside a mile north) helped to usher in a plethora of tourists to the otherwise sleepy agricultural hamlet of Dover Plains. By the 1830’s enough visitors were arriving to imbibe in the area’s natural splendor that hotels began popping up to accommodate them. The Stone Church Hotel, perhaps the most popular, was situated only “about a hundred rods from the Church.”[i] The scene at hand rarely disappointed. One visitor was so taken with the grandeur of the Seven Wells that he remarked that they “made up one of the most interestingly beautiful scenes that I have ever beheld.”[ii] Others were similarly smitten and prone to hyperbole. “Some are so deep,” one admirer wrote, “that one would fain be lowered into them to see the stars at noon.”[iii] Another person casually mentioned that some of the wells “are found to be several hundred feet deep.” This same individual in his description of the Wells and the Stone Church would later rapturously declare that “In viewing these objects of external nature, the mind rises above the material character of the structure to that Power who formed all things.”[iv]

Hemlock Falls While some ventured to the wells on semi-religious pilgrimages, others came for entertainment. The deep wells with their cool, crystal water were perfect aquariums for native brook trout. “We were met by a gentleman with a fishing-rod,” a tourist recorded, “who informed us that in some of these he found very excellent sport.”[v] Thomas Lossing, the son of Benson J. Lossing, the famous author and historian who lived in Dover up on Chestnut Ridge, regularly visited the Seven Wells. In Thomas’ memoir, My Heart Goes Home, he recounts a childhood visit in which he and a friend made a ladder of ropes and descended thirty feet into one of the wells to carve their names just above the waterline. The task took three hours. “The names could be seen ever afterward in the morning sunlight from the slope toward the well,” Thomas recalled.[vi] At the conclusion of Thomas Lossing’s narrative he wonders what his mother would have thought had she known what he was up to that day. His family always made a point to warn him about the wells. They weren’t being overprotective. Philip Smith in his General History of Dutchess County notes that “One of two fatal accidents are mentioned as having occurred here.”[vii] In fact, a relative of the family had died by falling into one “and it required the services of a diver to recover his body.”[viii] Making a close approach is generally ill-advised due to the strongly sloping nature of the land near the edges of the wells. In addition, a thick layer of slippery needles from white pines and hemlocks coat the ground surrounding the potholes, further compounding the risk of inadvertently tumbling into one. A sage piece of advice offered up by a traveler was to “Conduct the examination of the Wells from the bottom upward, for we found that it is not near so dangerous to go up precipitous places as to descend.”[ix] One source notes that “A young man named Germond, one of a picnic party, slipped from the bank and was drowned in one of the ‘Wells’ in 1844.”[x] This was likely Charles S. Germond. Records from the South Amenia Cemetery report the death of an 18-year-old by this name on October 2, 1844. Reports of Strange Creatures During the 19th century several baffling encounters took place around the Wells. On rare occasions visitors reported seeing what can best be described as an incredibly large snake within or near the seemingly bottomless basins. The first documented appearance of the creature took place in 1831 and was seen by Isaac Thompson, an old hunter who frequently navigated the slopes of West Mountain in pursuit of deer and other prey. While passing the wells one day he looked down into one of the larger wells and spotted a snake of herculean proportions reposing on a flat rock within a rod or two of a raging cataract. Thompson said the reptile was as large as a man and possessed a scaly head that matched the size and likeness of a bear. Shortly after being spotted, it entered the water and disappeared. In all his years in the woods he had never seen anything like it. In the 1850’s sightings dramatically increased and incensed locals began scratching their heads. One particularly chilling encounter took place in 1855. On a summer afternoon, a young man named George Lewis ventured to the Seven Wells with his younger sister to escape the stifling August heat. After following the brook up the mountain for about 1,000 feet the duo heard a strange noise, and upon turning their heads, saw the snake along the edge of the brook devouring some type of carcass that they said was similar in size to a dog. The creature had a thick red stripe running along its spine, Lewis reported, but otherwise boasted a dull coloration, blending in well with the surrounding leaf litter. Due to the sheer size of the creature, which they stated to be at least 10 or 12 feet in length and as thick as a pig, they quickly retreated back to town. Following the string of sightings attempts to locate the creature were undertaken, but to no avail. Whatever the almost larger than life beast was it appears to have been known to local Native Americans. In 1842, an octogenarian recalled that Indians generally avoided the place, believing the Seven Wells to be inhabited by some type of monster or fearsome deity. After the 1850’s reports began dwindling. It’s hard to say exactly what this mystery snake was. Rattlesnake dens are known in the area, but this species typically doesn’t venture near water and never attains a size as large as what was reported. Rattlesnakes rarely exceed 5 feet. The largest on record in New York State measured in at just under 75 inches (6.25 feet). Northern water snakes, while similar in length, are much thinner. It is difficult to believe that even the largest of either of these species could be mistaken for a beast on par with an anaconda. Might the witnesses, like some of those who reported the wells to be hundreds of feet deep, have exaggerated the size? It’s unlikely we’ll ever know for sure. All that we are certain of is that whatever lived along the margins of the Seven Wells Brook long ago plagued the town with a maelstrom of fear and anxiety that lived on long after the last sighting took place. Rare and Unique Flora Botanically speaking, the area surrounding the Seven Wells is of great interest. The shaded confines of the narrow valley caused by topography and the numerous evergreens that inhabit the area reduces the temperature enough to allow plants of more northern affinity to gain a foothold. In many ways the composition of flora here is reminiscent of the Catskills and Adirondacks. Plants typical of northern hardwood forests like mountain maple, red elderberry, and hobblebush thrive in this cool, moist oasis. Numerous spring wildflowers abound as well, ranging from the delightful purple fringed polygala to yellow trout lilies and pink lady slippers.

Manetta Cascade The Harlem Valley, unlike most parts of the region, possesses limestone and other rocks that are imbued with high quantities of calcium. This creates soil that’s neutral to alkaline. Plants fond of these conditions are known as “calciphiles” and can often be found in abundance where their needs are met. Many of these are quite rare. While the acidic needles from the evergreens along the Wells Brook increases the pH to an extent that limits their presence in the immediate vicinity, less than a mile away a preserve harbors numerous threatened and endangered plants that rely on neutral soils for survival. In early May of 1938, the Torrey Botanical Society embarked on a field trip to Seven Wells. Their most interesting find was a few specimens of eastern leatherwood, a rather uncommon shrub. They also intended to explore the environs of Stone Church that day, too. But as they followed the serpentine brook up the mountainside they discovered that the Seven Wells “proved more interesting than the short spectacular beauty of the Old Stone Church” and so they “left the latter spot out of the trip entirely.”[xi] While the Stone Church is generally credited as being the more scenic of the two spots many “think that the ‘Wells’ even surpass the ‘Church’ in interest.”[xii] The water from Wells Brooks has a remarkable purity to it and at one time was used as Dover Plain’s water supply. In September 1900, a group of 50 men under the direction of the Dover Plains Water Company began digging a ditch for the laying of pipe from the lower well to town. A 6-inch diameter pipe was installed. It was a rather simple gravity-fed design: “This company simply drops a slot in the hole and nature does the rest.”[xiii] This system stayed in place until 1958 when the town began looking for alternative sources of water to meet the needs of a growing town. In times of drought it was necessary to ration water from the vast natural reservoirs. Moreover, the amount of water for fire protection measures was deemed to be inadequate. Today, Dover utilizes a system of artesian wells. Sometime after 1917 the privately owned Seven Wells were closed to the general public. For over a hundred years the magnificent string of glacial potholes brooded in solitude, offering their grandeur only to the wild creatures of the forest and a few select individuals. In 2022, the Town of Dover, with funding from several environmental and land agencies, purchased the property the Wells sit on with the intention of making this historic landmark accessible to all. Now that both the Seven Wells and the Stone Church have finally been conserved, visitors venturing to the tranquil hamlet of Dover Plains can once again fully partake in a set of experiences first enjoyed more than two centuries ago. As an admirer penned in 1838, “If thou shouldst ever happen in Dutchess county, with a spare day, I would advise thee by all means to visit these two scenes.”[xiv]

This article is from my book, Hudson Valley History & Mystery, Volume 2. [i] Robert Sears, The Wonders of the World, in Nature, Art, and Mind (New York, NY: Robert Sears, 1842), 336. [ii] “A Visit to ‘The Stone Church’ and ‘The Wells,’” ed. Robert Smith, The Friend, vol. 12, no. 9, 1839, 67. [iii] Edward O. Dyer, Gnadensee: The Lake of Grace (Boston, MA: The Pilgrim Press, 1903), 231. [iv] “Dover Stone Church,” ed. T.S. Arthur and Virginia F. Townsend, Arthur’s Home Magazine, vol. 31, January-June 1868, 326. [v] Robert Sears, The Wonders of the World, in Nature, Art, and Mind (New York, NY: Robert Sears, 1842), 334. [vi] Thomas Sweet Lossing, My Heart Goes Home: A Hudson Valley Memoir, ed. Peter D. Hannaford, 1st ed. (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 1997), 102. [vii] Philip H. Smith, General History of Duchess County, From 1609 to 1876, Inclusive (Pawling, NY: Philip H. Smith, 1877), 150. [viii] Thomas Sweet Lossing, My Heart Goes Home: A Hudson Valley Memoir, ed. Peter D. Hannaford, 1st ed. (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 1997), 102. [ix] “A Visit to ‘The Stone Church’ and ‘The Wells,’” ed. Robert Smith, The Friend, vol. 12, no. 9, 1839, 67. [x] Arthur T. Benson, “Glimpses of Dover History,” Yearbook of the Dutchess County Historical Society, May 1914-April 1915, 24. [xi] George Dillman et al., “Field Trips of the Club,” Torreya, vol. 38, no. 4 (July/August 1938): 102. [xii] Arthur T. Benson, “Glimpses of Dover History,” Yearbook of the Dutchess County Historical Society, May 1914-April 1915, 24. [xiii] “Water at Dover Plains,” Putnam County Courier (Carmel, NY), October 12, 1900, 12. [xiv] “A Visit to ‘The Stone Church’ and ‘The Wells,’” ed. Robert Smith, The Friend, vol. 12, no. 9, 1839, 67.

Torrey's Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum torreyi)

Torrey’s Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum torreyi) Seven species of mountain mint (Pycnanthemum spp.) are found in New York. Of these, four are state listed as either threatened or endangered. These mountain mints include: blunt (P. muticum), whorled (P. verticillatum var. verticillatum), basil (P. clinopodioides), and Torrey’s (P. torreyi). Outside of New York, only the last two are widely regarded as rare. Range & Protective Status Torrey’s mountain mint currently ranges along the Appalachians from northern Georgia to New Hampshire. A southern arc extends from this same chain to the western reaches of Kentucky, Tennessee, and southern Illinois. There are only around 35 extant occurrences of this species. With such low numbers, it receives a G2 rating of “imperiled” on the global conservation scale. It is state endangered. While always rare, habitat loss caused by both development and succession, along with deer browse, has considerably reduced its range over the years. In New York, it is confined to the southeastern portion of the state where it continues to hold on in a few strongholds, such as in the southern Hudson Highlands. Habitat This species favors upland environments and can most frequently be found inhabiting dry, open woods or along forest margins. It performs best in sun-dappled conditions and can attain a height of over a meter. Plants situated in full sun are often stunted and the lack the lushness and vigor of those in shadier locales. At first glance, these stunted plants that can easily be mistaken for Virginia mountain mint (P. virginianum).

Identifying Characteristics Since many species in the genus Pycnanthemum look similar and possess relatively minor distinguishing characteristics, not to mention their often-great morphological variation and propensity to easily hybridize, it can be a challenge to positively identify this species. Recent work cataloging herbarium specimens has revealed that numerous specimens identified as Torrey’s mountain mint have been mislabeled. Most of these erroneous classifications have proven to be P. torreyi’s closest congener, whorled mountain mint (P. verticillatum). The prime identifying feature of Torrey’s mountain mint is its narrow lanceolate calyx teeth which range between 1.0-2.0 mm in length. Some sources indicate these are typically 1.0-1.5 mm; others, 1.5-2.0 mm. The calyx is actinomorphic or radially symmetric (not bilabiate). Whorled mountain mint has shorter, broader calyx teeth deltoid in shape that measure 0.5-1.0 mm. The florets of Torrey’s mountain mint usually have strongly exserted pollen-rich stamens, in contrast to the shorter and often abortive stamens of whorled mountain mint. Plants are in bloom from late June through September.

Another diagnostic feature is that the stem is covered with fine, uniformly distributed hairs on both the faces and angles. Other species have glabrous or densely hoary stems, or those with hairs more prominent on the stem angles. What’s more, the top of the leaves of P. torreyi are glabrous (vs. the canescence of P. verticillatum). The bottoms of the leaves are sparsely pubescent, usually following along the midvein. The leaf margins may be entire or possess a few low teeth. Narrow, lanceolate leaves are borne on short petioles. Leaf width does not surpass 1.5 cm. Whorled mountain mint generally has slightly wider leaves than P. torreyi.

Anne Hutchinson & Split Rock

Anne Hutchinson is one of the only important figures of early colonial America who was female. Throughout her nine-year residence in the New World she found herself constantly mired in controversy for her religious beliefs, eagerness to share them, and ultimately, the threat she posed to the established order. During her storied life she bore more than her fair share of criticism. Maligned to the extreme she had been labelled by New England elite “a dayngerous Instrument of the Divell raysed up by Sathan.” Her reputation has improved over the years, her name now synonymous with toleration and religious freedom. Where she lived and died statues have been erected and highways named in her honor. But unlike other famous figures from that era, few of us possess more than a cursory knowledge of who this woman was and what she stood for. In America, Anne’s story begins in 1634 in the heart of Puritan controlled Massachusetts. A recent emigrant from England, Anne and her husband William Hutchinson, a wealthy cloth merchant, settled in Boston. They lived in a spacious house directly across the street from the colony’s governor, John Winthrop. From the moment she boarded the ship that would take her across the Atlantic, Anne began voicing strong opinions that would eventually land her in court years later. During her ocean voyage, Anne’s unorthodox beliefs were overheard by a minister, and once landing in Massachusetts, she found herself having difficulty gaining admittance to the Puritan Church. But after reassuring church officials that she was, in fact, of like mind, they opened the doors to Anne and her family. In little time, however, she again began voicing opinions contrary to church dogma. Anne Hutchinson, like all Puritans, believed in the doctrine of predestination—that prior to birth God had chosen those who would be granted entry to heaven. The main staple of Puritan belief was the “Covenant of Grace.” Simply put, it stated that certain people were chosen or “elected” by God for salvation and there was nothing one could do to affect that either way. On the flip side, was the “Covenant of Works” which stressed that salvation could be earned by performing certain deeds or “works.” The latter covenant applied to biblical Adam, who, agreeing to abide by God’s laws, would be granted everlasting life as a reward—so long as he fulfilled his obligations. It was purely conditional. After the fall of Adam, this type of salvation went out the window, God alone now choosing who would receive salvation. This is the gist of Puritan belief in its simplest form and seems relatively straightforward. A working Puritan theology, however, is dizzyingly convoluted and complex and, at its surface, can be downright paradoxical. The Puritans set up a form of worship that tried to harmonize the two differing covenants. The Puritans believed that the “elect” were granted inherent grace, but there was an understanding that it was conditional, insomuch that the elect would be faithful to God and his laws. An elect, it was believed, was supplied by God with the wherewithal to fulfill the necessary obligations of faithfulness and obedience to keep the compact. In essence, a person was saved regardless of their actions, but there was a degree of human responsibility (even if God himself supplied it). The Reverend Cornelius Pronk, an expert on Puritan theology, writes, “For the Puritans the covenant of grace was both conditional and absolute and ultimately dependent upon the sovereignty of God’s action. Needless to say, this concept of a conditional yet absolute covenant created tensions.” These ideas were unsettling to many. If deeds truly have no bearing on one’s salvation then what incentive is there for people to make a conscious endeavor to act decently and moral if everything is already planned out as if a cosmic play? The Puritan Church decided to come up with a system to rectify this and detect the elect, and in the process, ensure order as the community strived to see if they were one of the lucky few to have received God’s grace. In effect, this also harmonized both covenants. Your salvation—or lack thereof—was chosen for you, but through industriousness of labor and diligence to church doctrine and scripture (works) it was hoped glimpses of one’s predetermined destiny would come to light through personal introspection. It was reasoned this process would help ease societal angst by providing individuals with something to strive for, thereby giving them a degree, however slight, of control over their lives. Everyone was eager to prove to themselves (and the community) that they were among the elect. Anne Hutchinson thought the church overly stressed the importance of these tenets, which she believed was tantamount to preaching a covenant of works. She believed that all one needed was an active faith that could be accessed inwardly by speaking directly to the Holy Spirit that resided in an elect’s heart and soul (this itself was revolutionary and heretical) and that salvation was purely unconditional. The reliance on churches, ministers, and scripture therefore weren’t needed to detect or “work” towards one’s salvation. The elect were simply guided by the voice of God within themselves; as such, they were not bound by laws or human institutions, but rather their own intuition and conscience. The church found this to be dangerous as it diminished their role and threatened the diligent works that were the pillar of Puritan society. John Winthrop thought this not only dangerous, but lazy, recording “it was a very easy and acceptable way to heaven—to see nothing, to have nothing, but wait for Christ to do all.” Anne’s harboring of these beliefs was disconcerting, but what landed her in hot water with the clergy was the influence she had on her peers. In 1636, Anne started to host meetings at her home with fellow parishioners. Here, she discussed and criticized sermons delivered by local ministers. As she accumulated standing and influence among society, she became emboldened and more freely began preaching her own ideas of salvation. At first only women were in attendance, but later men started visiting as well, including the newly elected governor, Henry Vane. At her peak, she held two meetings a week and attracted up to 80 people at each meeting. Eventually, the Puritan Church decided that something needed to be done about Anne before she caused a full-on schism. She was charged with 80 counts of heresy and put on trial in November 1637. John Winthrop presided over the hearing, having recently defeated Henry Vane for the governorship. Unlike his predecessor, Winthrop was no fan of Anne.

The Trial Winthrop laid the charges before Anne Hutchinson: “her ordinary meetings about religious exercises, her speeches in derogation of the ministers among us, and the weakening of the hands and hearts of the people towards them.” Anne’s first mistake was just preaching in general—in Puritan society women were not allowed to instruct in any religious matter hearkening back to Timothy 2:12, a biblical verse that states: “But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.” Out of all Christian denominations Puritans clung to scripture perhaps the most. Thus, it was a violation of the word of God for her to teach religious matters in any capacity. Anne followed through by quoting the example of put forth in Titus, saying the older women should instruct the younger. “All this I grant you,” Winthrop acknowledged, adding “But you must take it in this sense that elder women must instruct the younger about their business and to love their husbands and not to make them to clash.” Anne was stirring up trouble in regard to the patriarchy by making women disobedient to their husbands, and this could not be countenanced. Aside from the fact that she was a woman, the court took issue with her radical views. After the trial Winthrop would write that Anne’s meetings were “the pretence to repeat sermons, but when that was done she would comment upon the doctrines, and interpret all passages at her pleasure, and expound the dark places of Scripture.” Eventually, the court asked Anne directly her views on salvation, but she demurred by rather boldly stating “I did not come hither to answer questions of that sort.” While her beliefs were undoubtedly a major issue, court transcripts seem to place more concern on Anne’s insolence when it came to authority. Hutchinson’s tarnishing of the reputations of the clergy was one of the main charges brought forth. In her home meetings, Anne made them appear to be, as Winthrop put, “not able ministers of the gospel.” Her criticism was that most of the Puritan ministers were completely incapable of preaching a covenant of grace—amounting to saying they were not so misguided as they were inept. This would not be tolerated, and the court told her to “lay open yourself”—that is acknowledge her sins and ask for forgiveness. She did not. By the end of the second day of proceedings, in which Anne obviously became more bitter, she lashed out with an outburst in which she characterized herself as a prophet—and it was this that ultimately sealed her fate. In a rather lengthy address Anne proceeded to say that the Lord “did open unto me and give me to see that those which did not teach the new covenant had the spirit of the antichrist… he hath let me see which was the clear ministry and which the wrong.” All of this she had been shown “by an immediate revelation” from God. Coming from anyone this would be highly implausible, but the court found it even more absurd that the Almighty would reveal himself to a mere woman and not a minister, magistrate, other influential male member of Puritan society. At the end of her address she issued a dire warning: “if you go in this course you begin, you will bring a curse upon you and your posterity,” concluding with “and the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.” After listening to this the deputy governor, Thomas Dudley, issued an admonishment: “I am fully persuaded that Mrs. Hutchinson is deluded by the devil.” The governor was in agreement that this was a “delusion,” and after a vote among the members of the court, Anne was found guilty of the charges against her and banished from the colony. She was, as Winthrop put it, “a woman not fit for our society.” Before she was sent away Anne was placed under house arrest for several months until a second trial took place. This time she was excommunicated from the Puritan Church. Shortly thereafter, Governor Winthrop sent word for her to depart. In late March 1638, Anne and her family, along with around 30 other families who held similar religious views, headed south where they settled on Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay. Anne Hutchinson and her adherents, along with Roger Williams, who resided north in Providence, helped forge the religiously tolerant colony of Rhode Island. Here, Anne continued preaching. She remained there until 1642 when the harassment of Massachusetts officials became too much. Anne was informed that Massachusetts was looking to expand their boundaries, and would in little time, exert influence and control over her nascent colony. Scared of the threat of undergoing the same ordeal, if not worse, as before, she and her husband decided to uproot their large family again. William Hutchinson began scouting for a suitable location to settle in New Netherland, another religiously tolerant colony that was run by the Dutch. Far removed from the meddlesome hands of their harassers, they had hoped they would finally be free. The Hutchinson family briefly settled in Brooklyn. While here, they purchased a property in the northern Bronx and began improving the land. But before things were finished, William Hutchinson died suddenly in the fall of 1642. This left Anne with seven children to raise by herself. Despite the loss, Anne pushed forward and took over the running of things at the burgeoning homestead. Not long after her husband’s death she contracted a young carpenter by the name of James Sands and his partner to construct the family home. One day while Sands was working by himself, his partner having been sent on an errand to obtain more provisions, a group of rowdy Indians came calling. The house was merely framework at this time. The company made a loud commotion in an unknown tongue and proceeded to gather up the tools, placing an axe on Sands’ shoulder and other tools in his hands and then made motions for him to leave. They then departed to the nearby shore to collect clams and other shellfish. Undaunted, the carpenter resumed his work. A short while later, the Indians returned, gathering up the tools once more and making the same gestures for him to leave. Putting the tools down, he went back about his business with the Indians still there. They lingered awhile longer and then left without any further accostment to the carpenter. Eventually, Sands appeared to have taken the very clear message to heart, and after informing Anne of the situation, promptly departed, leaving the house unfinished. Anne simply hired another to complete the job and moved in. It is said that while in Rhode Island Anne had friendly relations with the local tribes and probably because of this she downplayed the incident. In any case, even if this did instill her with fear, she put her trust in God and continued things as usual.

Massacred By Indians One morning in the latter half of August 1643, an Indian “professing friendship” visited the family and, upon seeing the defenseless nature of farm, scurried back to his tribe to gather a handful of companions. They returned later that day, and obviously, professing friendship once more, convinced a person within the household to tie up the dogs. No sooner had the animals been restrained, the Indians began a massacre that ultimately resulted in the deaths of 16 people. Anne, her son-in-law, and all her children, save one, and some other individuals associated with the family, were brutally murdered. One account claims that a daughter “seeking to escape” was caught “as she was getting over a hedge, and they drew her back again by the hair of the head to the stump of a tree, and there cut off her head with a hatchet.” After the attack, the Indians piled the bodies into the house and set the dwelling on fire. The livestock were similarly corralled into the barns and these, too, set ablaze. The historian, Otto Hufeland, notes that the “whole settlement being so completely obliterated that up to the present time, no one has ever been able to locate even the site.” Now you might be asking, what brought about this terrible attack? It’s important to understand that Anne could not have picked a worse time to settle in New Netherland. Shortly after arriving to the colony, a conflict known as Kieft’s War erupted that brought significant enmity between the Indians and Dutch. The inept governor Willem Kieft first created tensions by demanding tribute payments from the local tribes, something that the Indians understandably rejected. Later, the killing of a settler by the Indians drove the governor to seek vengeance in which, ultimately, an entire village was mercilessly slaughtered by the Dutch at Pavonia in February 1643. Various tribes in the surrounding areas united against the Dutch and waited until after the harvest to seek significant retribution. Anne Hutchinson and her family may have been hapless casualties of war, or, possibly targeted for other reasons.

Conspiracy? There are conflicting accounts regarding the possession of the land on which the Hutchinsons resided—several say the Indians received no payment for the land and this is why the natives removed the settlers. However, records show that the Dutch government had paid the Indians for the land in 1640. Be that as it may, it’s possible these documents are fraudulent—essentially transactions committed to paper in which the Indians gave no consent. Whatever the case, the Indians claimed no payment was made. From these muddied waters, it’s hard to get a coherent grasp of the situation. Robert Bolton, the historian who wrote two volumes to Westchester County history, believed accounts contesting the legality of Dutch owned lands “looks…like a collusion between the New England authorities and the Indians.” In other words, New Englanders wanted the land held by the Dutch and used the unrest brought about by Kieft’s War as a pretense for a land grab. The Indians who undertook the attack were under the leadership of the preeminent sachem Uncas, a man “who had always been the unscrupulous ally of the English.” The war between the Dutch and Indians was one way to clear the land and make it available to properly devout Englishmen. The troublesome Anne Hutchinson and her heretic followers were considered enemies, same as the Dutch. The detailed account of the massacre helps give credence to this plot. Edward Johnson, the man who wrote the graphic account a decade after the massacre, was a military leader of the Massachusetts Bay colony. The firsthand knowledge makes it seem he, or another fellow Englishman, was at the scene of the attack. According to most accounts, the only survivor, aside from the Indians, was Anne’s daughter, Susanna. She was taken, legend has it, at Split Rock, and did not witness the massacre. Even if she had been present, she was an Indian captive for years, and it’s hard to believe such a detailed knowledge would be transmitted to Johnson, a family enemy. Johnson writes that another person from the household escaped “to tell the sad newes” of the massacre. John Winthrop’s journal entry refutes this (he had constantly been keeping tabs on Anne since the Massachusetts trial). Perhaps Johnson or a compatriot was the one who “fled” to relate the “sad” news.

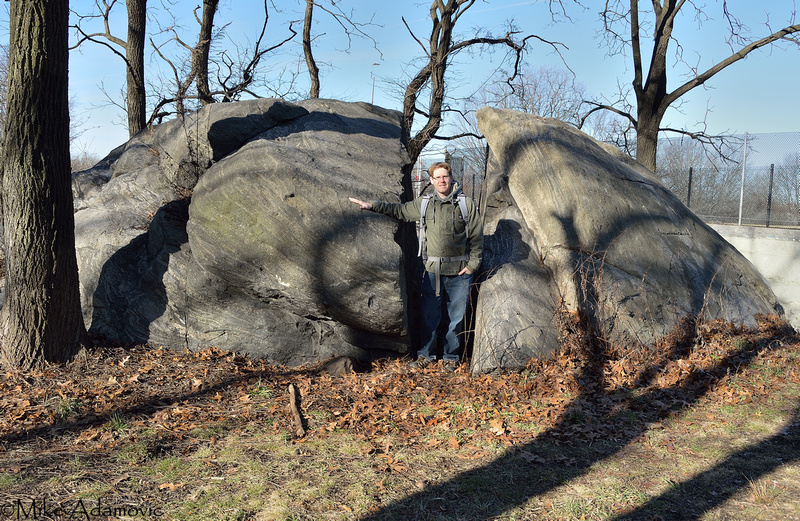

The author stands inside the cleft of Split Rock.

All of this casts doubt on the notion that the Hutchinson massacre was a random attack. It superficially appears that the raid was orchestrated by New Englanders bent on weakening the Dutch, deterring English dissidents from settling in New Netherland (and showing rather shrewdly what happens to heretics by the hand of “God”), all with the hope in mind that this would eventually shift dominion of the land to the authority of the English. This is all speculation, of course, but it is possible a cover up between the most influential men in Puritan New England took place. Unfortunately, from the scant evidence that exists, we’ll likely never know for sure. It’s believed that the Siwanoys, a branch of the Mohegans, were the ones that attacked the settlement that fateful late summer day. Wampage, a local leader, is said to have personally killed Anne Hutchinson. He later adopted a corruption of her name as his own, signing documents as “Ann Hoock.” Supposedly, it was a common Native American custom to change one’s name to commemorate an important or respected victim. He probably spared Susanna Hutchinson’s life because of her vibrant red hair, something which the Indians had never seen before. Legend dictates that Susanna was out picking blueberries at the time of the attack, and when she realized what was transpiring, hid in the sizable cleft of the nearby Split Rock, a prominent glacial erratic, or boulder. Despite the concealment, the Indians located her nevertheless, took her captive, and eventually adopted her as a member of the tribe. Purportedly, they called her “Fall Leaf” on account of her fiery locks. A journal entry of John Winthrop from July 1646, notes that when peace was concluded Susanna was returned to the Dutch. He notes that “She was about 8 years old when she was taken… and she had forgot her own language, and all her friends, and was loath to have come from the Indians.” In 1651, Susanna married the Bostoner John Cole, and like her mother, bore many children—11 in all. A few famous descendants include Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and the Bushes, along with the portrait painter John Singleton Copely. The site of the Hutchinson homestead has long been a mystery. For years, it was believed to have been very near the site of Split Rock in the northern part of present-day Pelham Bay Park, and at one time, a plaque on the boulder stated this. However, a number of theories place it at alternate locations. Robert Bolton wrote that the residence “appears to have been situated on Pelham neck, formerly called Ann’s hoeck, literally Ann’s point or neck.” Because Wampage adopted Anne’s name as his own, and his grave is said to be in a mound on the southeastern tip of Pelham Point, along with that of another important sachem, Chief Ninham, it’s likely the land was named after the Indian, rather than having an association with the actual Anne Hutchinson. Otto Hufeland, in his 1929 work, Anne Hutchinson in the Wilderness, has convincingly shown that Anne’s homestead sat southwest of Split Rock in the present-day site of Co-op City, though its exact location is unknown.

A view of Co-op City in the distance from the pedestrian footpath leading to Split Rock.

In May 1911, a bronze plaque was installed at Split Rock stating among other things that Anne Hucthinson “Sought Freedom from Persecution in New Netherland Near this Rock.” The funds for the plaque were raised by the Colonial Dames of the State of New York. Over 100 people attended the unveiling ceremony that included a handful of speakers, one of them being a descendant of Joseph Weld, the man who owned the house that Anne was imprisoned in while awaiting her second trial. The plaque was stolen in 1914, and although it was supposedly replaced, it is conspicuously missing today. A shallow rectangular hole on the boulder marks its placement. Split Rock was almost destroyed in 1958 as Interstate 95 was being constructed, the east bound lane being set to pass directly through the famous landmark. However, a historian and a group of concerned citizens ultimately persuaded the engineers to move the path of the highway a few feet to the north. While the landmark has been saved it now sits isolated on a small triangular traffic island between I-95 and an exit ramp of the Hutchinson River Parkway. A neglected footpath that passes under I-95 is the only legal way to access it. It receives few visitors. Though it is periodically tagged with graffiti, those who care for this stone and its storied past, meticulously remove the paint and restore it to its former glory. Standing at Split Rock today inhaling potent diesel fumes and listening to the swooshing of heavy traffic as cars and trucks speed furiously by, it’s difficult to imagine how pleasant this spot once actually was. Images from the 1800’s and early 1900’s show dapper gentleman in suits and ladies in opulent dresses standing beside or atop the boulder. Some came here for picnics, others to take in the history or gawk at the mighty boulder and wonder what fantastic force of nature could have cleaved it asunder. Many activities that were once able to take place here are now as the ghosts that are reputed to roam around Split Rock and the Pelham Bay Park.

Legends & Lore A newspaper article titled “Legends of Pelham” from 1901 says Anne’s oldest son managed to escape from the massacre “only to be burned at the stake in front of Split Rock.” The glow of the fire and screams of the tortured spirit were, in times past, said to sometimes present themselves to passersby during dusk. The entire park and surrounding area is saturated with legend and lore. On the eastern flanks of the park down by the shores of Long Island Sound is Cedar Knoll. Before the area was colonized by Europeans, a “severe and sanguinary battle” between the Matinecocks and Siwanoys took place here, resulting in the defeat of the latter. The victors reputedly decapitated their enemies. Headless Indian spirits now eternally roam the scene of their defeat. A report from an elderly woman in early 1900’s stated she saw these ghosts with her own eyes during her childhood, after which, she never ventured back to the haunted Cedar Knoll. She described them as being “the most awful ghosts you can possibly imagine.” They only appear during the full moon. She recounts: “There were more than a score of them, and they had no heads unless you count the heads which they were carrying in their hands…They formed in a big ring, and began to dance…Then, they threw their heads in the centre of the ring and danced around them.” To many Native American tribes split rocks or those with conspicuous fissures in them were often reputed to be a portal to the spirit world. Several other similarly sized monoliths in the surrounding area were said to be of spiritual or religious importance, such as Grey Mare on Hunter Island. While no documentation exists as to Split Rock’s status, it’s likely it did serve as a focal point of worship to local Indians.

According to legend, Susanna Hutchinson hid in this crevice.

Split Rock Road, now fragmented by I-95, was once the scene of the Battle of Pell’s Point on October 18, 1776. Patriot forces hid behind stone walls along the road to surprise British and Hessian forces. The Americans slowed down the enemy enough for a successful retreat by George Washington and his troops, where they were ultimately able to regroup at White Plains. The phantom sounds of running feet are sometimes heard along the Siwanoy Trail, thought to be the ghost of an Indian girl that ran up Split Rock Road to inform the Americans of the British approach. Pelham Bay Park may have some contemporary ghosts as well. The isolated nature of the park and vast stretches of marshland make it a perfect area to conceal murder victims. From 1986-1992 more than 40 bodies were recovered from the park. Animal sacrifices are also routinely performed here as well by practicers of Afro-Caribbean religions. Some police officers theorize that the vast quantity of Indian burials throughout the park are partially responsible for drawing in both murderers and worshippers. Perhaps the spirits are trying to attract additional companions. Today we remember Anne Hutchinson more for her courage than her religious beliefs. It’s hard not to admire this woman who underwent so much tribulation for something she believed in. Rather than be silenced she spoke her mind regardless of the consequences. Despite being banished from Massachusetts, her persecution never stopped, and she eventually met with the ultimate misfortune because of it. New England elite and aggrieved Native Americans tried to obliterate all traces of Anne Hutchinson. They partially succeeded, but like a soul or an idea, some things are impossible to kill. She split, she fractured, the status quo—perhaps it’s fitting we associate Anne with the gargantuan Split Rock. What else could be more fitting a tombstone for a woman larger than life?

Getting There: The only legal way to access Split Rock (40.886512, -73.815017) is by following a pedestrian footpath that passes underneath and along Interstate 95. The entrance to the path is located directly across the street from 3480 Eastchester Place, Bronx, NY 10475. Follow the path for a third of a mile to the landmark.

Hummingbirds & Native PlantsFew birds draw as much love and fascination as do the diminutive hummingbirds. There’s something innately magical in both their appearance and habit that profoundly captivates. Adding to the intrigue is that our experiences with them tend to be exceedingly fleeting. Normally, we get but a momentary glimpse of these mesmerizing birds before they disappear in a blink of an eye to a new patch of ground where they again tirelessly dart from flower to flower with lightning speed and precision. Why such the hurry? Hummingbirds are in a constant race against the clock to acquire enough nectar to sustain their ludicrously high metabolisms. It takes a great deal of energy to power wings that are flapped 50-80 times a second, on average. Hummingbirds must visit one to two thousand flowers a day. Habitat fragmentation is posing challenges to hummingbirds when it comes to meeting their daily quotas. It is therefore imperative that homeowners, landowners, and anyone else with a little extra space do what they can to alleviate the increasing strain. While putting up feeders is a good start, it’s better yet to plant flowers that hummingbirds commonly visit. Aside from the latter option being decidedly more natural, native plants support protein-rich insects. Like nectar, insects are an important component of a hummingbird’s diet. Nectar provides much needed energy, but furnishes none of the protein necessary to forge muscles and the like. While there are numerous species of hummingbirds across America, only the ruby-throated hummingbird ranges east of the Mississippi River. Lucky for us, this species also happens to be one of the most attractive. Males of the species, true to their name, boast a vibrant ruby to garnet colored gorget that covers most of their diminutive throats.

Hummingbirds are most attracted to long, tubular flowers that have a red, pink, or orange coloration. Flowers don’t have to be particularly fragrant, as these birds are drawn to color rather than scent. Many species sporting red flowers are especially adapted for pollination by hummingbirds—the sleek, slender beaks of these birds fit perfectly into many of the blossoms, allowing access to deep nectar reserves which few other creatures can obtain without cheating the system. In this case, both plant and animal have coevolved, thus a decline in one will invariably result in a reduction of the other. Take red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) for instance. Flowers of this species are like dangling bells—only hovering creatures with exceedingly long tongues stand a chance of obtaining the rich, yellow nectar at the end of inch-long spurs. This common and often prolific wildflower is one of the most important plants for ruby-throats as they migrate north in the spring. So important, in fact, that their ranges in the eastern U.S. closely overlap. These hummingbirds have a difficult time colonizing areas where columbine is absent, as acceptable food supplies during the early days of the year are often severely limited.

In addition to planting flowers of the correct coloration and shape, it’s best to clump rather than widely space. Aggregations are more readily spotted and prevents the birds from having to furiously zig-zag across the garden, expending time and energy in the process. Moreover, keeping the hummingbirds in one place for a longer duration proves especially useful if you’re keen on watching them as they feed. The ideal hummingbird garden is one that is in continuous bloom, providing nectar from May to September. Selecting species that will enable the garden to provide for birds over a wide temporal period is the best way to help ensure at least a bird or two will stay put in your area and not just pass through. If you provide most of their caloric needs, there’s often little reason for them to leave your floral oasis until they must migrate back south towards the end of summer. Below, I’ve provided a list of species that support hummingbirds in the Northeast. It’s far from exhaustive but does highlight some of the most relished plants. I would caution against exclusively selecting hybrids and cultivars. In many cases, flowers of these provide less nectar than the straight species. When it comes to ‘Fan Scarlet,’ a hybrid of cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) and great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica) that resembles the former in appearance, there’s an 80% reduction in nectar than that found in natural populations of L. cardinalis. The cardinal flower cultivar ‘Fried Green Tomatoes’ also has nectar levels below that of the straight species. As you can see, one must be wary when choosing plants for anything other than just general appearance. To ensure nectar production remains relatively consistent, be sure to have at least a handful plants in the garden that are straight species, thereby creating high genetic diversity. While some plants will produce less, others will produce more, which means the population will have a stable average. Aside from doing meticulous research into the nectar production of each cultivar, this is the only sure way to guarantee that you’re adequately providing for our tiny avian friends.

Spring: *Red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) Redbud (Cercis canadensis) Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera) Fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis) Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) Moss phlox (Phlox subulata) *Azaleas (Rhododendron spp.)

Early Summer/Mid-Summer: *Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans) Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) Lilies (Lilium spp.) *Honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.) *Oswego tea (Monarda didyma) Wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) Beardtongues (Penstemon spp.) Rosebay rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum)

Late Summer/Early Autumn: *Jewelweeds (Impatiens capensis & pallida) New England blazing star (Liatris novae-angliae) *Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

*Those marked with an asterisk are especially favored.

Spring in Northeastern Woodlands

Though the initial signs of spring are at first slight, the dead and dull landscape quickly transforms into a vibrant patchwork of multi-hued color upon the first significant warm spell. From the latter half of March to early May, depending on the weather and climate of the area, the first bit of color to emerge is among the upper reaches of the forest. Buds of various species begin to swell with the increased warmth and typically display dullish tints of red or red-brown, that as the early spring season progresses, produces a haze that hangs over the landscape. Red maples produce the most vibrant show by means of their tiny, yet vivid red—and to a minor extent—yellow flowers. When it comes to our native trees, few associate them with flowers, except, of course, when it comes to the showy dogwoods, redbuds, and tulip trees. But most trees do put on a floral show, though most are rather inconspicuous. While the flowers of the red maple are small, many tree species have even tinier blossoms that lack much in the way in pigment and are pale green or yellow, and also lack the general shape of what the average person would consider a flower. Walking under a red maple and gazing up at the branches, one can see thousands of roundish clusters that look like dots in some abstract painting of the pointillistic type. Closer inspection reveals these "dots" are made up of multiple blossoms. This species produces separate male and female flowers. While most red maples bear flowers of only one sex, some trees do possess both, though each gender is typically confined to a separate branch.

The larger, more perfectly round clusters are male. Each individual flower contains at least a dozen pollen-bearing anthers. At first emergence the anthers are pale red, but as they gradually rise up, supported atop a long, wiry filament they turn yellow from the exuded pollen. Females, by contrast, are compact. While less obvious from a distance, close-up, they rival their male counterparts in elegance. The stigmas of the females are a rich red and have a texture of the purest velvet.

Wind pollination increases in frequency as latitude increases. First, it's generally windier in northern locales. But more importantly, the diversity of trees is much lower in higher latitudes. For the best odds of fertilization, it's necessary to have as few impediments as possible. In the north, where there are comparatively few species, pure stands of a single species often exist and pollen transfer is readily guaranteed. But in the tropics, where diversity is high, and plants of the same species may be extremely scattered, pollen given to the wind would likely never reach its intended target. Conifers, along with some angiosperms, utilize this primitive pollination system. It can be seen best in the Adirondacks, White Mountains, and other northern reaches of the region that are occupied by boreal and transitional forests. In late spring it's a mistake to park your car beneath these pollen-laden trees. Only a handful of them are needed to create billowing sheets of golden fog that thickly coat everything around when spring gusts rush through the branches. Oaks, willows, and alders are also wind pollinated. These deciduous species have pollen attached to long, drooping flower clusters called catkins which dangle from the ends of branches. Red maples are primarily pollinated by insects, but pollen is also carried by the wind to a minor extent.

Shortly after the first trees begin to awaken, the wildflowers of the understory are also roused from their long slumber, eager to bloom before the overarching trees leaf out and steal precious light. In quick succession, woodland spring ephemerals put on displays as magnificent as a 4th of July firework show. Those who wish to view this anticipated and fleeting spectacle must be quick about getting out. Some species are in bloom but a day or two before the wind and rain takes the petals away, as is the case with the fragile bloodroot. Spring ephemerals, like most plants, follow a regimented blooming pattern that varies very little from year to year in terms of sequence. The first to make an appearance is the unimpressive skunk cabbage. Apart from lacking flowers with any remarkable éclat, crushed portions of the plant emit an unpleasant odor much as the name implies. While skunk cabbages usually make an appearance during the latter half of March, sometimes they appear significantly earlier. I've seen this plant poke its head out along the edges of mucky streams during early February in the midst of the most minor of thaws. This may seem highly unusual for the normally dainty wildflowers, but the skunk cabbage isn't like other spring ephemerals. The flowers, which are partially hidden inside a cone-like structure called a spathe, are merely tiny dots studded across what resembles a rotten egg, both in sight and scent. For this, "the plebian skunk cabbage...ought scarcely to be reckoned among true flowers," according to Neltje Blanchan, an early 20th century wildflower expert. They also exhibit a unique trait in the plant world known as thermogenesis, which is why it's possible for such an early bloom date when other plants are still trapped below the frozen ground. This trait allows skunk cabbages to produce heat, similarly to warm-blooded animals. With generated temperatures rising to 90° F, it's easy for them to melt their way through standing snow and ice.

Hepatica usually opens its buds just after coltsfoot appears. Despite the nearly concurrent displays, these species are rarely seen together. Hepatica grows among the interior of moist woodlands. Its multiple color morphs ranging from pure white to pink to the deepest violet stand out among the stark environs of the leaf-littered understory. "When at the maturity of its charms, it is certainly the gem of the woods," the naturalist John Burroughs once admiringly wrote. Two forms of hepatica exist in the eastern U.S., primarily differentiated by leaf shape. Blunt-lobed hepatica has rounded, or blunt leaves, while those of the sharp-lobed variety come to a point at the tip. Apart from physical characteristics, habitat preferences differ as well. The blunt-lobed form typically inhabits upland environments with acidic soil; sharp-lobed hepatica is found more often in moist lowlands, containing richer and more neutral soil. These two varieties, or subspecies, were once considered to be distinct species, but over the years taxonomists have revised their opinions, deciding that these differences aren't substantial enough to warrant a completely separate classification.

Right around the time hepatica is in bloom the mottled leaves of the trout lily start to emerge along gravelly riverine plains and throughout damp forests generally not far from a wetland or other water source. While the leaves appear early, the yellow flowers lag behind a couple weeks, blooming usually around the middle of April. Trout lilies, like numerous other spring ephemerals, are able to produce blossoms so early in the spring season through use of the energy reserves stored in the root-like corms. Expansive, long-lived colonies often develop. The average age of most colonies is about 150; some have been recorded to be as much as 1,300 years old. Though these plants often carpet the forest floor in the thousands with their artsy leaves, don't expect to come across a sea of yellow flowers. It's been estimated that only 1% of plants will bloom. This is probably because trout lilies rely more on vegetative propagation than reproducing by means of seeds. Up until the early days of the 20th century, this plant boasted a plethora of names, a few of which, really didn't fit the plant at all. "It is a pity that this graceful and abundant flower," John Burroughs lamented, "has no good and appropriate common name." "Dog-tooth violet" and "adder's-tongue" were most frequently used. He put forth a flurry of theories as to why these names were bestowed. In terms of the dog-tooth violet appellation, he theorized that the color and shape of the unopened buds resembled canine teeth; yet the violet part puzzled him, as it "has not one feature of a violet." Others have suggested it was so-called due to the shape of the plant's corms. Adder's-tongue, he thought, derived from the "spotted character of the leaf," because it vaguely resembles the patterns on the skin of some snakes. Neltje Blanchan, on the other hand, proposed that the name came about from the "sharp purplish point" of young plants as they first emerge above ground, clearly resembling a little serpentine tongue. Burroughs propounded the name trout lily, and is generally credited with its now widespread use. In his book, Riverby, he concisely stated: "It blooms along the trout streams, and its leaf is as mottled as a trout's back." He was also fond of "fawn lily" too—again, in relation to the spotted nature of the leaves.

Before the blossoms of the trout lily can be seen gently nodding in the early spring breezes, seemingly still drowsy from their winter torpor, arguably the most stunning ephemeral of the spring season rises quickly and gracefully from the newly softened ground. Bloodroot, whose ivory petals surround a bright, golden center is one of the most short-lived of our wildflowers. Within a day or two of surfacing, the single bud produced by each plant opens, and senescences within a similar time frame. Seed pods soon develop and swell, sitting atop the stem like an inverted watermelon. Like several other spring ephemerals, bloodroot uses ants as a means of seed dispersal, a technique known as myrmecochory. Attached to each tiny seed is a fleshy appendage called an elaiosome that’s rich in protein and lipids, but serves no direct impact to the seed’s survival. Like the sweet nectar of a flower, these elaiosomes are tempting treats to insects. Ants, in particular, are readily enticed to collect them. Once dragged back to the colony, the energy-laden accessory is removed for consumption, and the hard seed body is dumped in waste pits that provide an enriched medium for growth. In this way, bloodroot is able to colonize new locales away from the parent plant and ensure optimal germination. While new colonies are formed from seeds, and preexisting ones receive a supplemental boost, tightly knit colonies are a result of vegetative propagation, another form of reproduction which produces clones by extension of rhizomes.

The large blossoms, as well as the glaucous, almost succulent leaves, create a striking scene among the withered foliage and broken stems of last year’s growth. A particularly large, showy colony is easily spotted at a considerable distance and visually eclipses other ephemeral populations that attain a similar size. There’s something entrancing and fairy-like in the demeanor of these somewhat uncommon flowers, with their unique ability to pop-up seemingly overnight, transforming the landscape like magic. Such vigor and color contrasts greatly with the bleak debris that surrounds, creating an image of unsurpassed beauty that’s sure to be emblazoned in memory and sought out year after year. As the name portrays, these plants do indeed possess crimson roots. Moreover, this species bleeds the same as any injured animal. A broken leaf or stem causes the plant to exude a fluid alarmingly similar to blood. It stains anything it touches, and has been used in years past as a dye by both Native Americans and colonists.

Wild violets are perhaps the least appreciated of our wildflowers. Though often distracted by other showier and perhaps rarer flowers, the common, yet regal violets, are a fascinating genus to delve into, and shouldn’t automatically be dismissed solely due to their profusion. While many violets share numerous similarities and are extremely difficult to differentiate from one another, it has been estimated that there are, in fact, between 500-600 species worldwide, approximately 85 of which can be found growing in North America. There’s tremendous variation among the community, with many varieties garnering oxymoronic names, such as round-leaved yellow violet and sweet white violet. While a majority do live up to their names in appearance, there’s more than a few that are anything but violet, being completely white, and even the brightest shade of yellow, with numerous combinations and levels of mixing. Yellow violets appear to be the most primitive, with their flowers being the first shift away from the ancestral green. Purple, in contrast, is thought to be one of the most advanced colors. Evolution in progress can be witnessed in the Canada violet, a native to Canada and the eastern U.S. Many botanists speculate that the mostly white flower, often dabbed with minor purplish tingeing on the back of the petals, is transitioning from entirely white to “violet.”

Once fertilization has occurred by means of insects or self-pollination, the seeds are ready for an explosive dispersal. After the seeds are fully developed, the pods they’re stored in slowly dry out, with the pod gradually tightening around the seeds, building up tension in the process, similarly to the action of a spring. Later, when the pods are disturbed, or sometimes just randomly, the pressure becomes too great and the seeds are shot out like miniature cannonballs. Amazingly, seeds are capable of being flung up to 15 feet away from the parent plant. Insects aren’t the only ones to appreciate the tasty nature of the violet. Nearly all parts of the plants are edible for human consumption. The leafy greens can be collected to create a salad that’s high in vitamins A and C, superseding that of an equal quantity of oranges. Beginning in the 19th century, candied violets gained favor as a dessert garnishment and were widely served. Though their popularity has decreased over the years, in some circles they're still a favorite topping for sweet dishes of cake or ice cream. Traditionally, a syrup was also made by boiling the flowers in a concoction of sugar. Apart from sweetening the lips, the syrup is useful as a substitute for litmus paper. The solution turns red in the presence of an acid, green for a base.

Red columbine is a wide-ranging perennial that occupies the eastern half of the United States. Flowers are typically 1.5 inches long and borne on plants growing 1-2 feet tall. This species has an affinity for slightly alkaline to neutral soil. It’s able to thrive in places most other plants can’t even gain a minor foothold. It’s not uncommon to find a copious profusion of flowers sprouting from a vertical cliff face. The roots are able to penetrate the tiniest of cracks and subsist on the barest amounts of soil. Columbine is also likely to be found gracing spongy beds of moss within open and somewhat sunny forests. Red flowers throughout temperate forests are usually rather scarce. In many cases, this color appears to have evolved to attract hummingbirds. The long, tubular structures of the columbine flowers attest to this. Nectar is sequestered at the base of each lengthy tube; only creatures with long beaks or tongues are able to reach it. It has been speculated that the yellow underside is a mechanism to guide potential pollinators to the sweet reward. Apart from hummingbirds, bumblebees are probably one of the few other pollinators able to access it. Some insects, however, may cheat the system and chew a hole through the flower to rob it of nectar, similarly to Dutchman’s breeches—in such a case, flowers fail to be pollinated.

It's wise to be on the lookout for the tightly clustered bluets, which true to their name are mostly of an azure or sky-blue hue and often grace sunny pastures and meadows, along with sprouting along the edges of woodland hiking trails where abundant light penetrates to the ground. And then there's the delicate dwarf ginseng, which closely resembles its rare and exploited relative, American ginseng. The dwarf is exceedingly more common, on account of it lacking the size and potency of its larger cousin, and thus never having been collected in meaningful numbers. On high hills and low mountains, the tall corydalises thrive on dry, rocky ledges. Pink flowers are borne on the common species, golden on the rare. Plants with an affinity for alkaline soils are generally rarer than their acid loving brethren in the Northeast. Part of the reason for this is that alkaline habitats are relatively scarce, a result of the underlying geology of the region. The wild purple clematis, a delicate flowering vine producing blue-purple flowers with a crepe paper look, prefers to vegetate around damp rocky habitats, such as talus slopes and cliff sides that possess more basic or alkaline pH. Twin-leaf, a plant in many ways identical to bloodroot, except for its higher pH preference and that each leaf is bisected and looks like a pair of butterfly wings, is rather rare and is on the threatened or endangered plant lists of New York and New Jersey. As the spring ephemerals wrap things up for the season, the shrubs and trees begin their leafy show, draping all the landscape in the soft verdure that we that we take delight in seeing, knowing the warm and pleasant days of summer can't be far behind. Shrubs are the first to leaf out after the herbaceous layer of the understory. A layering effect takes place, with the lowest awakening first and the highest last. Come the height of summer when the canopy is fully expanded, sunlight reaching the secondary layers gets progressively smaller as one continues to descend. It's been estimated that only between 1-5% of solar radiation penetrates through to the forest floor. Plants of the understory compensate for the lack of summer light by gaining a head start in the spring. Unfortunately, the earliest shrubs to begin leafing are exotic species, such as Japanese barberry and honeysuckle. This is detrimental to some ephemerals who are shaded out prematurely by the often times prolific invaders that not only block light, but steal nutrients and considerably alter the environment in other ways.

« Older Posts

© Adamovic Nature Photography

|