Anne Hutchinson & Split Rock

Anne Hutchinson is one of the only important figures of early colonial America who was female. Throughout her nine-year residence in the New World she found herself constantly mired in controversy for her religious beliefs, eagerness to share them, and ultimately, the threat she posed to the established order. During her storied life she bore more than her fair share of criticism. Maligned to the extreme she had been labelled by New England elite “a dayngerous Instrument of the Divell raysed up by Sathan.” Her reputation has improved over the years, her name now synonymous with toleration and religious freedom. Where she lived and died statues have been erected and highways named in her honor. But unlike other famous figures from that era, few of us possess more than a cursory knowledge of who this woman was and what she stood for.

In America, Anne’s story begins in 1634 in the heart of Puritan controlled Massachusetts. A recent emigrant from England, Anne and her husband William Hutchinson, a wealthy cloth merchant, settled in Boston. They lived in a spacious house directly across the street from the colony’s governor, John Winthrop. From the moment she boarded the ship that would take her across the Atlantic, Anne began voicing strong opinions that would eventually land her in court years later. During her ocean voyage, Anne’s unorthodox beliefs were overheard by a minister, and once landing in Massachusetts, she found herself having difficulty gaining admittance to the Puritan Church. But after reassuring church officials that she was, in fact, of like mind, they opened the doors to Anne and her family. In little time, however, she again began voicing opinions contrary to church dogma.

Anne Hutchinson, like all Puritans, believed in the doctrine of predestination—that prior to birth God had chosen those who would be granted entry to heaven. The main staple of Puritan belief was the “Covenant of Grace.” Simply put, it stated that certain people were chosen or “elected” by God for salvation and there was nothing one could do to affect that either way. On the flip side, was the “Covenant of Works” which stressed that salvation could be earned by performing certain deeds or “works.” The latter covenant applied to biblical Adam, who, agreeing to abide by God’s laws, would be granted everlasting life as a reward—so long as he fulfilled his obligations. It was purely conditional. After the fall of Adam, this type of salvation went out the window, God alone now choosing who would receive salvation. This is the gist of Puritan belief in its simplest form and seems relatively straightforward. A working Puritan theology, however, is dizzyingly convoluted and complex and, at its surface, can be downright paradoxical. The Puritans set up a form of worship that tried to harmonize the two differing covenants.

The Puritans believed that the “elect” were granted inherent grace, but there was an understanding that it was conditional, insomuch that the elect would be faithful to God and his laws. An elect, it was believed, was supplied by God with the wherewithal to fulfill the necessary obligations of faithfulness and obedience to keep the compact. In essence, a person was saved regardless of their actions, but there was a degree of human responsibility (even if God himself supplied it). The Reverend Cornelius Pronk, an expert on Puritan theology, writes, “For the Puritans the covenant of grace was both conditional and absolute and ultimately dependent upon the sovereignty of God’s action. Needless to say, this concept of a conditional yet absolute covenant created tensions.”

These ideas were unsettling to many. If deeds truly have no bearing on one’s salvation then what incentive is there for people to make a conscious endeavor to act decently and moral if everything is already planned out as if a cosmic play? The Puritan Church decided to come up with a system to rectify this and detect the elect, and in the process, ensure order as the community strived to see if they were one of the lucky few to have received God’s grace. In effect, this also harmonized both covenants. Your salvation—or lack thereof—was chosen for you, but through industriousness of labor and diligence to church doctrine and scripture (works) it was hoped glimpses of one’s predetermined destiny would come to light through personal introspection. It was reasoned this process would help ease societal angst by providing individuals with something to strive for, thereby giving them a degree, however slight, of control over their lives. Everyone was eager to prove to themselves (and the community) that they were among the elect.

Anne Hutchinson thought the church overly stressed the importance of these tenets, which she believed was tantamount to preaching a covenant of works. She believed that all one needed was an active faith that could be accessed inwardly by speaking directly to the Holy Spirit that resided in an elect’s heart and soul (this itself was revolutionary and heretical) and that salvation was purely unconditional. The reliance on churches, ministers, and scripture therefore weren’t needed to detect or “work” towards one’s salvation. The elect were simply guided by the voice of God within themselves; as such, they were not bound by laws or human institutions, but rather their own intuition and conscience. The church found this to be dangerous as it diminished their role and threatened the diligent works that were the pillar of Puritan society. John Winthrop thought this not only dangerous, but lazy, recording “it was a very easy and acceptable way to heaven—to see nothing, to have nothing, but wait for Christ to do all.”

Anne’s harboring of these beliefs was disconcerting, but what landed her in hot water with the clergy was the influence she had on her peers. In 1636, Anne started to host meetings at her home with fellow parishioners. Here, she discussed and criticized sermons delivered by local ministers. As she accumulated standing and influence among society, she became emboldened and more freely began preaching her own ideas of salvation. At first only women were in attendance, but later men started visiting as well, including the newly elected governor, Henry Vane. At her peak, she held two meetings a week and attracted up to 80 people at each meeting.

Eventually, the Puritan Church decided that something needed to be done about Anne before she caused a full-on schism. She was charged with 80 counts of heresy and put on trial in November 1637. John Winthrop presided over the hearing, having recently defeated Henry Vane for the governorship. Unlike his predecessor, Winthrop was no fan of Anne.

The Trial

Winthrop laid the charges before Anne Hutchinson: “her ordinary meetings about religious exercises, her speeches in derogation of the ministers among us, and the weakening of the hands and hearts of the people towards them.” Anne’s first mistake was just preaching in general—in Puritan society women were not allowed to instruct in any religious matter hearkening back to Timothy 2:12, a biblical verse that states: “But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.” Out of all Christian denominations Puritans clung to scripture perhaps the most. Thus, it was a violation of the word of God for her to teach religious matters in any capacity. Anne followed through by quoting the example of put forth in Titus, saying the older women should instruct the younger. “All this I grant you,” Winthrop acknowledged, adding “But you must take it in this sense that elder women must instruct the younger about their business and to love their husbands and not to make them to clash.” Anne was stirring up trouble in regard to the patriarchy by making women disobedient to their husbands, and this could not be countenanced. Aside from the fact that she was a woman, the court took issue with her radical views. After the trial Winthrop would write that Anne’s meetings were “the pretence to repeat sermons, but when that was done she would comment upon the doctrines, and interpret all passages at her pleasure, and expound the dark places of Scripture.”

Eventually, the court asked Anne directly her views on salvation, but she demurred by rather boldly stating “I did not come hither to answer questions of that sort.” While her beliefs were undoubtedly a major issue, court transcripts seem to place more concern on Anne’s insolence when it came to authority. Hutchinson’s tarnishing of the reputations of the clergy was one of the main charges brought forth. In her home meetings, Anne made them appear to be, as Winthrop put, “not able ministers of the gospel.” Her criticism was that most of the Puritan ministers were completely incapable of preaching a covenant of grace—amounting to saying they were not so misguided as they were inept. This would not be tolerated, and the court told her to “lay open yourself”—that is acknowledge her sins and ask for forgiveness. She did not. By the end of the second day of proceedings, in which Anne obviously became more bitter, she lashed out with an outburst in which she characterized herself as a prophet—and it was this that ultimately sealed her fate.

In a rather lengthy address Anne proceeded to say that the Lord “did open unto me and give me to see that those which did not teach the new covenant had the spirit of the antichrist… he hath let me see which was the clear ministry and which the wrong.” All of this she had been shown “by an immediate revelation” from God. Coming from anyone this would be highly implausible, but the court found it even more absurd that the Almighty would reveal himself to a mere woman and not a minister, magistrate, other influential male member of Puritan society. At the end of her address she issued a dire warning: “if you go in this course you begin, you will bring a curse upon you and your posterity,” concluding with “and the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.”

After listening to this the deputy governor, Thomas Dudley, issued an admonishment: “I am fully persuaded that Mrs. Hutchinson is deluded by the devil.” The governor was in agreement that this was a “delusion,” and after a vote among the members of the court, Anne was found guilty of the charges against her and banished from the colony. She was, as Winthrop put it, “a woman not fit for our society.”

Before she was sent away Anne was placed under house arrest for several months until a second trial took place. This time she was excommunicated from the Puritan Church. Shortly thereafter, Governor Winthrop sent word for her to depart. In late March 1638, Anne and her family, along with around 30 other families who held similar religious views, headed south where they settled on Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay. Anne Hutchinson and her adherents, along with Roger Williams, who resided north in Providence, helped forge the religiously tolerant colony of Rhode Island. Here, Anne continued preaching. She remained there until 1642 when the harassment of Massachusetts officials became too much. Anne was informed that Massachusetts was looking to expand their boundaries, and would in little time, exert influence and control over her nascent colony. Scared of the threat of undergoing the same ordeal, if not worse, as before, she and her husband decided to uproot their large family again. William Hutchinson began scouting for a suitable location to settle in New Netherland, another religiously tolerant colony that was run by the Dutch. Far removed from the meddlesome hands of their harassers, they had hoped they would finally be free.

The Hutchinson family briefly settled in Brooklyn. While here, they purchased a property in the northern Bronx and began improving the land. But before things were finished, William Hutchinson died suddenly in the fall of 1642. This left Anne with seven children to raise by herself. Despite the loss, Anne pushed forward and took over the running of things at the burgeoning homestead. Not long after her husband’s death she contracted a young carpenter by the name of James Sands and his partner to construct the family home.

One day while Sands was working by himself, his partner having been sent on an errand to obtain more provisions, a group of rowdy Indians came calling. The house was merely framework at this time. The company made a loud commotion in an unknown tongue and proceeded to gather up the tools, placing an axe on Sands’ shoulder and other tools in his hands and then made motions for him to leave. They then departed to the nearby shore to collect clams and other shellfish. Undaunted, the carpenter resumed his work. A short while later, the Indians returned, gathering up the tools once more and making the same gestures for him to leave. Putting the tools down, he went back about his business with the Indians still there. They lingered awhile longer and then left without any further accostment to the carpenter. Eventually, Sands appeared to have taken the very clear message to heart, and after informing Anne of the situation, promptly departed, leaving the house unfinished. Anne simply hired another to complete the job and moved in.

It is said that while in Rhode Island Anne had friendly relations with the local tribes and probably because of this she downplayed the incident. In any case, even if this did instill her with fear, she put her trust in God and continued things as usual.

Massacred By Indians

One morning in the latter half of August 1643, an Indian “professing friendship” visited the family and, upon seeing the defenseless nature of farm, scurried back to his tribe to gather a handful of companions. They returned later that day, and obviously, professing friendship once more, convinced a person within the household to tie up the dogs. No sooner had the animals been restrained, the Indians began a massacre that ultimately resulted in the deaths of 16 people. Anne, her son-in-law, and all her children, save one, and some other individuals associated with the family, were brutally murdered. One account claims that a daughter “seeking to escape” was caught “as she was getting over a hedge, and they drew her back again by the hair of the head to the stump of a tree, and there cut off her head with a hatchet.” After the attack, the Indians piled the bodies into the house and set the dwelling on fire. The livestock were similarly corralled into the barns and these, too, set ablaze. The historian, Otto Hufeland, notes that the “whole settlement being so completely obliterated that up to the present time, no one has ever been able to locate even the site.”

Now you might be asking, what brought about this terrible attack? It’s important to understand that Anne could not have picked a worse time to settle in New Netherland. Shortly after arriving to the colony, a conflict known as Kieft’s War erupted that brought significant enmity between the Indians and Dutch. The inept governor Willem Kieft first created tensions by demanding tribute payments from the local tribes, something that the Indians understandably rejected. Later, the killing of a settler by the Indians drove the governor to seek vengeance in which, ultimately, an entire village was mercilessly slaughtered by the Dutch at Pavonia in February 1643. Various tribes in the surrounding areas united against the Dutch and waited until after the harvest to seek significant retribution. Anne Hutchinson and her family may have been hapless casualties of war, or, possibly targeted for other reasons.

Conspiracy?

There are conflicting accounts regarding the possession of the land on which the Hutchinsons resided—several say the Indians received no payment for the land and this is why the natives removed the settlers. However, records show that the Dutch government had paid the Indians for the land in 1640. Be that as it may, it’s possible these documents are fraudulent—essentially transactions committed to paper in which the Indians gave no consent. Whatever the case, the Indians claimed no payment was made. From these muddied waters, it’s hard to get a coherent grasp of the situation. Robert Bolton, the historian who wrote two volumes to Westchester County history, believed accounts contesting the legality of Dutch owned lands “looks…like a collusion between the New England authorities and the Indians.” In other words, New Englanders wanted the land held by the Dutch and used the unrest brought about by Kieft’s War as a pretense for a land grab. The Indians who undertook the attack were under the leadership of the preeminent sachem Uncas, a man “who had always been the unscrupulous ally of the English.”

The war between the Dutch and Indians was one way to clear the land and make it available to properly devout Englishmen. The troublesome Anne Hutchinson and her heretic followers were considered enemies, same as the Dutch. The detailed account of the massacre helps give credence to this plot. Edward Johnson, the man who wrote the graphic account a decade after the massacre, was a military leader of the Massachusetts Bay colony. The firsthand knowledge makes it seem he, or another fellow Englishman, was at the scene of the attack. According to most accounts, the only survivor, aside from the Indians, was Anne’s daughter, Susanna. She was taken, legend has it, at Split Rock, and did not witness the massacre. Even if she had been present, she was an Indian captive for years, and it’s hard to believe such a detailed knowledge would be transmitted to Johnson, a family enemy. Johnson writes that another person from the household escaped “to tell the sad newes” of the massacre. John Winthrop’s journal entry refutes this (he had constantly been keeping tabs on Anne since the Massachusetts trial). Perhaps Johnson or a compatriot was the one who “fled” to relate the “sad” news.

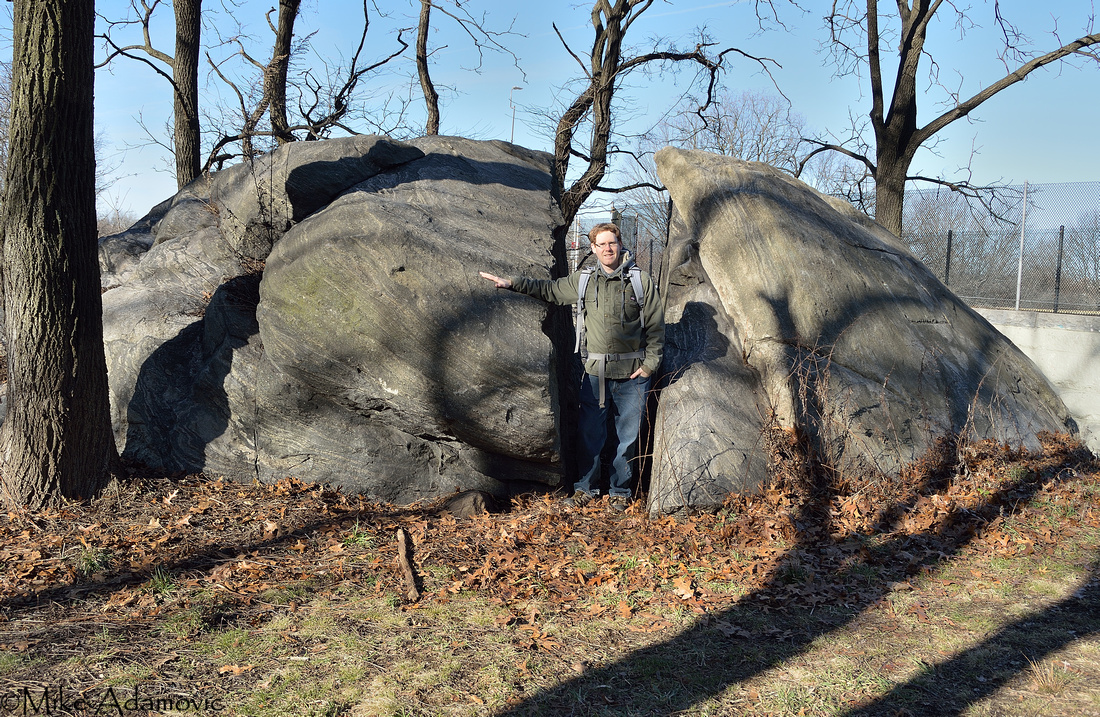

The author stands inside the cleft of Split Rock.

All of this casts doubt on the notion that the Hutchinson massacre was a random attack. It superficially appears that the raid was orchestrated by New Englanders bent on weakening the Dutch, deterring English dissidents from settling in New Netherland (and showing rather shrewdly what happens to heretics by the hand of “God”), all with the hope in mind that this would eventually shift dominion of the land to the authority of the English. This is all speculation, of course, but it is possible a cover up between the most influential men in Puritan New England took place. Unfortunately, from the scant evidence that exists, we’ll likely never know for sure.

It’s believed that the Siwanoys, a branch of the Mohegans, were the ones that attacked the settlement that fateful late summer day. Wampage, a local leader, is said to have personally killed Anne Hutchinson. He later adopted a corruption of her name as his own, signing documents as “Ann Hoock.” Supposedly, it was a common Native American custom to change one’s name to commemorate an important or respected victim. He probably spared Susanna Hutchinson’s life because of her vibrant red hair, something which the Indians had never seen before. Legend dictates that Susanna was out picking blueberries at the time of the attack, and when she realized what was transpiring, hid in the sizable cleft of the nearby Split Rock, a prominent glacial erratic, or boulder. Despite the concealment, the Indians located her nevertheless, took her captive, and eventually adopted her as a member of the tribe. Purportedly, they called her “Fall Leaf” on account of her fiery locks. A journal entry of John Winthrop from July 1646, notes that when peace was concluded Susanna was returned to the Dutch. He notes that “She was about 8 years old when she was taken… and she had forgot her own language, and all her friends, and was loath to have come from the Indians.” In 1651, Susanna married the Bostoner John Cole, and like her mother, bore many children—11 in all. A few famous descendants include Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and the Bushes, along with the portrait painter John Singleton Copely.

The site of the Hutchinson homestead has long been a mystery. For years, it was believed to have been very near the site of Split Rock in the northern part of present-day Pelham Bay Park, and at one time, a plaque on the boulder stated this. However, a number of theories place it at alternate locations. Robert Bolton wrote that the residence “appears to have been situated on Pelham neck, formerly called Ann’s hoeck, literally Ann’s point or neck.” Because Wampage adopted Anne’s name as his own, and his grave is said to be in a mound on the southeastern tip of Pelham Point, along with that of another important sachem, Chief Ninham, it’s likely the land was named after the Indian, rather than having an association with the actual Anne Hutchinson. Otto Hufeland, in his 1929 work, Anne Hutchinson in the Wilderness, has convincingly shown that Anne’s homestead sat southwest of Split Rock in the present-day site of Co-op City, though its exact location is unknown.

A view of Co-op City in the distance from the pedestrian footpath leading to Split Rock.

In May 1911, a bronze plaque was installed at Split Rock stating among other things that Anne Hucthinson “Sought Freedom from Persecution in New Netherland Near this Rock.” The funds for the plaque were raised by the Colonial Dames of the State of New York. Over 100 people attended the unveiling ceremony that included a handful of speakers, one of them being a descendant of Joseph Weld, the man who owned the house that Anne was imprisoned in while awaiting her second trial. The plaque was stolen in 1914, and although it was supposedly replaced, it is conspicuously missing today. A shallow rectangular hole on the boulder marks its placement.

Split Rock was almost destroyed in 1958 as Interstate 95 was being constructed, the east bound lane being set to pass directly through the famous landmark. However, a historian and a group of concerned citizens ultimately persuaded the engineers to move the path of the highway a few feet to the north. While the landmark has been saved it now sits isolated on a small triangular traffic island between I-95 and an exit ramp of the Hutchinson River Parkway. A neglected footpath that passes under I-95 is the only legal way to access it. It receives few visitors. Though it is periodically tagged with graffiti, those who care for this stone and its storied past, meticulously remove the paint and restore it to its former glory. Standing at Split Rock today inhaling potent diesel fumes and listening to the swooshing of heavy traffic as cars and trucks speed furiously by, it’s difficult to imagine how pleasant this spot once actually was. Images from the 1800’s and early 1900’s show dapper gentleman in suits and ladies in opulent dresses standing beside or atop the boulder. Some came here for picnics, others to take in the history or gawk at the mighty boulder and wonder what fantastic force of nature could have cleaved it asunder. Many activities that were once able to take place here are now as the ghosts that are reputed to roam around Split Rock and the Pelham Bay Park.

Legends & Lore

A newspaper article titled “Legends of Pelham” from 1901 says Anne’s oldest son managed to escape from the massacre “only to be burned at the stake in front of Split Rock.” The glow of the fire and screams of the tortured spirit were, in times past, said to sometimes present themselves to passersby during dusk.

The entire park and surrounding area is saturated with legend and lore. On the eastern flanks of the park down by the shores of Long Island Sound is Cedar Knoll. Before the area was colonized by Europeans, a “severe and sanguinary battle” between the Matinecocks and Siwanoys took place here, resulting in the defeat of the latter. The victors reputedly decapitated their enemies. Headless Indian spirits now eternally roam the scene of their defeat. A report from an elderly woman in early 1900’s stated she saw these ghosts with her own eyes during her childhood, after which, she never ventured back to the haunted Cedar Knoll. She described them as being “the most awful ghosts you can possibly imagine.” They only appear during the full moon. She recounts: “There were more than a score of them, and they had no heads unless you count the heads which they were carrying in their hands…They formed in a big ring, and began to dance…Then, they threw their heads in the centre of the ring and danced around them.”

To many Native American tribes split rocks or those with conspicuous fissures in them were often reputed to be a portal to the spirit world. Several other similarly sized monoliths in the surrounding area were said to be of spiritual or religious importance, such as Grey Mare on Hunter Island. While no documentation exists as to Split Rock’s status, it’s likely it did serve as a focal point of worship to local Indians.

According to legend, Susanna Hutchinson hid in this crevice.

Split Rock Road, now fragmented by I-95, was once the scene of the Battle of Pell’s Point on October 18, 1776. Patriot forces hid behind stone walls along the road to surprise British and Hessian forces. The Americans slowed down the enemy enough for a successful retreat by George Washington and his troops, where they were ultimately able to regroup at White Plains. The phantom sounds of running feet are sometimes heard along the Siwanoy Trail, thought to be the ghost of an Indian girl that ran up Split Rock Road to inform the Americans of the British approach.

Pelham Bay Park may have some contemporary ghosts as well. The isolated nature of the park and vast stretches of marshland make it a perfect area to conceal murder victims. From 1986-1992 more than 40 bodies were recovered from the park. Animal sacrifices are also routinely performed here as well by practicers of Afro-Caribbean religions. Some police officers theorize that the vast quantity of Indian burials throughout the park are partially responsible for drawing in both murderers and worshippers. Perhaps the spirits are trying to attract additional companions.

Today we remember Anne Hutchinson more for her courage than her religious beliefs. It’s hard not to admire this woman who underwent so much tribulation for something she believed in. Rather than be silenced she spoke her mind regardless of the consequences. Despite being banished from Massachusetts, her persecution never stopped, and she eventually met with the ultimate misfortune because of it. New England elite and aggrieved Native Americans tried to obliterate all traces of Anne Hutchinson. They partially succeeded, but like a soul or an idea, some things are impossible to kill. She split, she fractured, the status quo—perhaps it’s fitting we associate Anne with the gargantuan Split Rock. What else could be more fitting a tombstone for a woman larger than life?

Getting There:

The only legal way to access Split Rock (40.886512, -73.815017) is by following a pedestrian footpath that passes underneath and along Interstate 95. The entrance to the path is located directly across the street from 3480 Eastchester Place, Bronx, NY 10475. Follow the path for a third of a mile to the landmark.

Comments

https://tv.starcheckin.com/@dinapulley090?page=about

http://219.151.182.80:3000/isobelehret697/isobel2018/wiki/How+To+turn+Alexander+Casino+Promotions+Into+Success

http://118.190.88.23:8888/jaydenteakle58

https://occultgram.icu/owenblacklock

https://cmt.tqz.mybluehostin.me/employer/casinohub-365/

http://106.15.120.127:3000/ieyalbert59491

https://git-web.phomecoming.com/marylou70j511

https://g.fzfengzhi.cn/barbwzk9818994

https://seferpanim.com/read-blog/32057_3-issues-twitter-desires-yout-to-forget-about-fat-pirate-gambling.html

http://git.eyesee8.com/trudiwrenn593/3751bizzocasino-777.com/issues/1

http://huamonarch.xyz:21116/lyndonencarnac

https://atflat.ge/agents/pamelamacdevit/

http://120.77.205.30:9998/tashakidd9341/1918cupom-bons/wiki/Best-Slots-Bons-Casino-Tips-You-Will-Read-This-Year

http://115.29.148.71:3000/sallydahms171

http://www.tengenstudio.com:3000/clintonporras

https://eufashionshoeclub.com/read-blog/5114_bounceball8-ang-nakakabighaning-laro-na-sumikat-noong-2000s-kasaysayan-gameplay.html

https://ai.florist/read-blog/69413_corals-online-betting-and-the-mel-gibson-effect.html

https://konkandream.com/author/iazkeeley74717/

https://git.dpark.io/hildredraphael

http://123.54.1.214:8418/maritzavbn8411

https://gitlab.oc3.ru/u/pedrogilruth3

https://git.fram.i.ng/augusta48z4559

https://jobhaiti.net/employer/happy-tiger-365/

https://ttemployment.com/employer/astronaut-crash-game-365/

http://47.119.121.249:3000/jaycarothers78

https://gitea.uchung.com/wildasommer93/wilda2003/wiki/A-Deadly-Mistake-Uncovered-on-Acessar-Bons-And-How-to-Avoid-It

https://git.7milch.com/faerawls679439

https://isabelzarate.com/darwinpalumbo

http://74.48.174.77:3000/shannansiede68

https://code.ioms.cc/christiecastle

https://www.buyjapanproperty.jp/author/rorycorser0602/

https://reswis.com/author/sharylkuntz805/

https://dev8.webserver5.com/employer/frumzi-777/

http://acc.jkard.com/read-blog/7843_seguranca-e-confianca-no-1bet4win-casino-e-fiavel-apostar.html

https://git.dpark.io/eartharobichau

https://dev.tcsystem.at/codyfrye334214

https://tiwaripropmart.com/author/kristinacranwe/

https://airealtorgroup.com/author/traceyj3670216/

http://182.92.157.29:6001/angelikaringle

https://www.jukiwa.co.ke/estate_agent/eliseneace168/

https://csirealestateinternational.com/author/deliahertz8077/

http://118.24.46.223:3000/gerardpilgrim

http://47.111.17.177:3000/henrybreeze715

http://8.130.52.45/adfrodger54041

http://51.15.222.43/claudettesamps/big-bass-splash-777.com3718/issues/1

https://gitea.katiethe.dev/vetapaquin0705

https://git.4lcap.com/concettamuntz7

https://realtyinvestmart.in/agent/genesisbrune08/

http://gitea.ucarmesin.de/cesarcarbajal6/3013069/wiki/Ten-Highly-effective-Tips-That-can-assist-you-888-Starz-Enregistrement-Higher

https://www.cinnamongrouplimited.co.uk/agent/tamarahicks397/