The Colorful Lobelias

During the latter half of the summer season flowers of the genus Lobelia first make their appearance, adding gaudy splashes of color to the overwhelmingly verdant surroundings that take hold of the landscape after the last of the vibrant spring ephemerals have faded away and before the tawny autumnal tints arrive. Coming in an unusually varied and vivid bunch, the hues garnered by this genus can easily be mistaken as originating from some foreign or tropical locale, particularly when it comes to cardinal flower and great blue lobelia, the brightest and showiest of the group, which resemble imported garden escapees. But, in reality, these vibrant reds and blues that glow as brightly as neon lights in our seemingly tempered forests and wetlands are in fact native to the U.S. Awarded the honor of “America’s favorite” by Roger Tory Peterson in his wildflower field guide, it’s easy to see why the fiery-red cardinal flower has gained such an impressive reputation. Standing between 2-5 feet tall with a color brighter than even the bird endowed with the same name, it’s unlikely to go unnoticed. Moreover, each plant usually bears a dozen or more blossoms along the plant’s slender spike that rises above all surrounding herbaceous vegetation; such floral extravagance “dazzles you,” as Thoreau voiced. John Burroughs, another poet-naturalist, in upstate New York, was similarly impressed with the species—enough so to write a poem about the cardinal flower in which he described the vivid plant a “heart-throb of color.”

This color comes in handy for attracting ruby-throated hummingbirds, the cardinal flower’s chief pollinator and sole hummingbird species native to the Northeast. As one of the few northern plants possessing red flowers—the hummingbirds color of choice—it’s the main reason these birds have been able to successively colonize our region. Both species find themselves mutually reliant on one another, and, not surprisingly, therefore have closely overlapping ranges. A decline of either species will inevitably result in a similar loss for the other. The shape of the tubular flowers have evolved to facilitate pollination by long-tongued creatures. Aside from hummingbirds, butterflies appear to be the only other pollinator capable of extracting the deeply sequestered nectar. The derivation of the plant’s name is not what you might think. While it’s tempting to conclude that the flower was named after the scarlet bird, or vice-versa, the naming of both actually harkens back to Europe. Clerics of the Catholic Church, called cardinals, wear cloaks of an identical hue—whence comes the name. On the other side of the color spectrum lies the great blue lobelia, a plant hardly less impressive than its scarlet-tinted cousin, sporting flowers imbued with a twilight azure of fading evening skies. Eloise Butler, an early 20th Century botanist, describes it filling late summer meadows “in such opulence” that the surroundings morph into an artwork seemingly “gemmed with lapis lazuli and rimmed with goldenrod.” This species is smaller, but more robust than the slender 3-6 foot tall cardinal flower, having its inch long blossoms more tightly packed and condensed. With these concentrated features its color presentation is dramatic and indeed gem-like.

As red attracts hummingbirds, blue, it seems, is the prime color to draw bees. Evolutionary speaking, it’s generally thought to be the most advanced flower color. Green emerged first, and then with a linear progression, white and yellow, red, and lastly the deep and enigmatic blues, developed. While bees are the main pollinators, hummingbirds will pay the occasional visit, although the stouter flowers favor pollination by the former. The plant’s Latin name, siphilatica, is in reference to it having been used in years past as a treatment for syphilis. Native Americans held its efficacy in high enough esteem that enterprising colonizers had it exported overseas. European physicians, however, failed to find it of any use.

Various tribes also believed it to possess magical qualities. Legend has it that if L. siphilatica is dried, ground into powder, and thrown into the winds of an approaching storm, it has the power to render them benign. The Iroquois steeped the plant in hot water and drank a concoction of it at night to ward off spells and other bewitchments. Lobelia inflata, commonly known as Indian tobacco, is another related species which has been used for a multitude of restorative purposes. Unlike the name suggests, the plant was not recreationally used; it was smoked only occasionally for medicinal purposes. Aboriginal inhabitants employed it mainly to treat asthma and other lung ailments. Ironically, modern research has shown the plant contains an alkaloid which has the potential to help smokers quit.

Its other chief use was as an emetic, meaning it induces vomiting. Other names for the plant consist of gagroot, puke and vomitweed. The plant has such an acrid taste that even the most ravenous livestock will avoid it. The ever-curious Thoreau himself tried the plant once noting that “tasting one such herb convinces me that there are such things as drugs which may either kill or cure.” A tea made from the leaves is so potent that in 1879 a Canadian farmer was confident enough in the plant’s ability to cause vomiting that he was recorded as humorously betting a team of horses that drinking the liquid would do the trick. Numerous historical accounts attest to its efficacy for such purgative purposes. Indian tobacco’s diminutive ¼ inch long flowers are studded along the length of the upright spike with a density much lower than the lobelias already described and bear a purple pastel coloration. Due to these factors, it’s by far the most frequently overlooked in the bunch, although its distinctive inflated seed pods, similar in appearance to small unripe grapes, make it easy pick out among a mass of vegetation. Though prized more for its medicinal merits than its beauty, an up-close look at its finely crafted blossoms is sure to draw admiration and respect. All three plants can be found in bloom from August to September. Indian tobacco arrives a bit sooner, sometimes as early as mid-July and thrives in drier woodland habitats less conducive to its soggy-dwelling brethren. It’s not unusual to spot individuals growing in thin soils along rocky trails on the sides of mostly xeric mountains. Cardinal flower and great blue lobelia, in contrast, prefer much moister environs, usually inhabiting the borders of streams, rivers, and other perpetually damp areas offering abundant sunlight. It’s certainly not much of a challenge to find these plants in areas in which they grow. All stand tall and erect with an air of confidence, matured from the flowers of spring that barely rear their shy heads above the detritus of the forest floor. As the year progresses each successive burst of flowering plants must reach higher than their predecessors if they wish to be seen and pollinated. They must keep in step with the ever-rising herbaceous vegetation that surrounds, consisting mostly of grasses and weeds, which by the time the lobelias put forth flowers can reach waist height or higher. With all the energy these plants have to expend to outcompete their duller competitors, it would be a shame to have such visually impressive displays be for naught. Get out there and search—it takes only a fraction of the time to find these common beauties than it would to locate rarer species endowed with a similar level of elegance.

Other local lobelias:

Pale-spiked lobelia (Lobelia spicata)

Kalm's Lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

Groundnut (Apios americana)

The groundnut (Apios americana) is a rather unusual specimen in the plant world, possessing an eclectic set of characteristics rarely seen bundled together in a single species. The roots, or rather tubers, have been used as a staple food source for millennia by the various indigenous tribes of North America. The adventuring naturalist, Henry David Thoreau, who partook in some wild specimens dug along the sloping sides of a sunny railroad embankment regarded it as a “fabulous fruit” with a “sweetish taste” that was “better boiled than roasted.” Its dark red or chocolate colored blossoms not only impress visually, but have one of the most fragrant scents of our native wildflowers. The delicate compound leaves, moreover, make an excellent groundcover that provides protection for a myriad of beneficial pollinating insects. The plump tubers also enrich the soil through a series of chemical and microbial reactions by a process known as nitrogen fixation. In short, groundnut, is one of the few native plant species that will satisfy the strictest requirements of even the most demanding gardener or plant enthusiast. This long-lasting perennial vine prefers full sun and very moist, acidic soil. It has a wide distribution, occupying 2/3 of the country, ranging from Maine westward to Colorado. Under the right conditions, plants can proliferate to provide an expansive groundcover, or if grown near a trellis or other similar upright structure, a dense wall of decorative foliage. Plants, generally speaking, do well grown at home, as long as the proper moisture conditions are met. The quickest way for a population to become established is to utilize tubers rather than seeds. Tubers should be harvested in the fall when plants go into dormancy. Seeds from the bean-like seed pods can also be collected at around the same time, although propagation is often difficult. Whatever method preferred, space individuals 12-18 inches apart, as to leave ample room to expand. Groundnuts can be grown around other similarly dense herbaceous plants or shrubs, such as violets, raspberries, strawberries, and blueberries. With the added nitrogen groundnuts put into the soil, surrounding plants receive a nutrient boost that helps increase size, and, if fruit producing, crop yield.

Despite groundnut’s prodigious resume, its widest accolade is undoubtedly its ability to be used as a wild edible. It has a fine taste resembling a potato. Tuber size is variable, with some younger specimens being no larger than a peanut; on rare occasions, that they can attain sizes comparable to an apple or even a melon. Nutritionally speaking, the groundnut is one of the richest wild plants. It’s high in carbohydrates and protein levels are found in three times the proportion as an equal quantity of potatoes. Historical reports indicate that nearly every indigenous culture within the distribution of A. americana used it as a source of food on some level. The Pilgrims were taught of its value by the natives of Massachusetts, which undoubtedly helped them survive their first harsh winter in the New World. Despite their value, groundnuts have never successfully proliferated as a staple crop. With plants taking a minimum of 2-3 years to produce tubers large enough and in sufficient quantities to gather, while potatoes can be harvested in a single season, it doesn’t make sense to grow commercially. Additionally, plants have a tendency to grow outward in every direction, making cultivating them in straight rows rather tricky. The atypical flowers of the groundnut make this species a curiosity to behold in any setting with its vastly unique shape, color, and scent. “The crumpled red velvety blossoms,” as Thoreau described, exhibit an inflorescence, often occurring in tall, upright clusters containing a dozen or more flowers that are thrust several inches above the foliage. The maroon-brown flowers which bloom from June to September are imbued with a delightful fragrance that permeates the air, and is somewhat similar in scent to violets, though much more potent and lasting (unlike the fleeting scent of the violet which contains a compound that temporarily inhibits smell receptors). A horticulturist at the turn of the 20th century pithily remarked that the groundnut “pays its tithe in fragrance, and brings into uniformity much that would be otherwise, unsightly, straggling growth.”

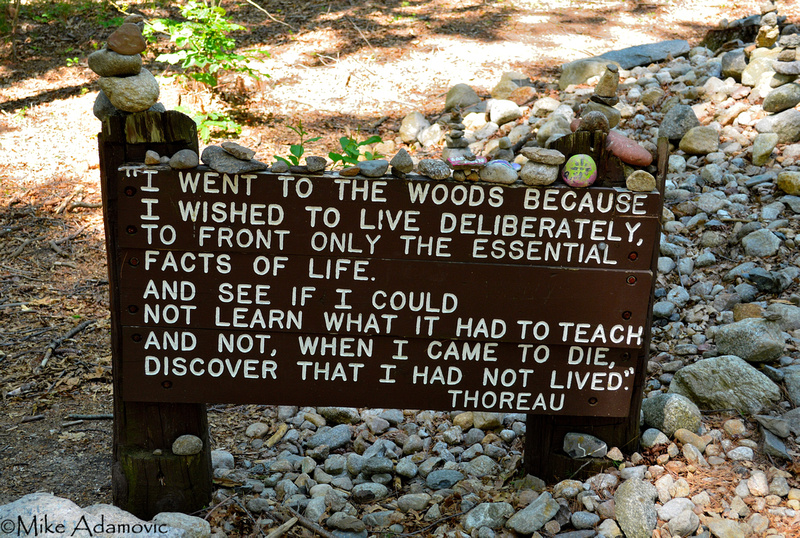

Transcendental Musings

It’s often forgotten that every natural object is imbued with an inherent beauty—that there’s more to a pleasing outdoor scene than delicately manicured lawns and gardens lined with gaudy phalanxes of tulips and plush beds of the ubiquitous daffodils or other accustomed garden denizens. That even the mundane when placed into its proper setting, as a rivet or bolt is positioned in a machine, has its purpose and importance. The lone and asymmetrical stone, aggregations of mushrooms, and swarming insects, give greater depth and fuel the scene at hand. Artificial displays excised of anything other than that reared by man can only drive my thoughts so far, leaving but the shallowest and most transitory of impressions. The unkempt and broad splendors of the natural world, in contrast, leave more than lingering awe, continuously driving curiosity and excitement as a new scene of wonder constantly unfolds before me. Among the forests, atop the woody hills and harsh mountain summits, and in every other wild place where nature reigns rather than lurks, a divinely intoxicating influence suffuses the air as thickly as fog, as intensely as light. It humbles, it inspires, it enraptures. The mind becomes more volatile and effervescent, whimsical even. All subjugating thoughts are lifted and evaporated into the crisp air. No longer preoccupied and worried by trivial matters, where a long standing bout of perennial tunnel vision has caused all peripheral sights to be glossed over, the landscape expands—trees can be picked out of the forest line, and individual leaves and blades of grass inspected among the mass of green, the eye drawn by subtle spotting or unusual coloration. Detail is at last seen. Curiosity buds. We become as nimble as a fox, as eagle-eyed as a raptor. We are in our element. A kindred sympathy develops between all surrounding life and matter encountered. The interpenetrating complexity overwhelms, shattering our egos and sense of understanding; all we can do is marvel at the surrounding beauty.

The experiences I’ve had where not even the most minor trace of humanity could be detected have been the most remarkable and memorable. The lapse of time separating me from these events of significance often stretch back years, but I have little difficulty remembering where it matters. Vivid sunsets and even the poignant smell of a wildflower have been enough to imprint the day in full detail into memory. In these instances where nature latches onto us, however slight, the undiluted energy of nature is easily absorbed. Its power cannot be easily contained. Try as you will, but it can’t be hoarded or sequestered for long. It’s eager to be transferred to the nearest object, like an electric spark, making the full rounds of the earth. It floods and expands in the body like lightning shooting from cloud to cloud, forming vast networks as comprehensive as those created by the roots of plants. Man is its surface conduit. From him it radiates by tendrils, which grasp and climb everything within reach, elevating man, and granting him new and inspiring views of both sight and thought. No longer disconnected, bouncing around as some rattling and discordant component, we now humbly assist with the workings of this grand machine, that we call Nature. *** Men vainly strive for a greater purpose, thinking only of advancement, the attainment of power and exerting influence—always on the move and shamefully hiding their heads if they’re surpassed by those more adroit than themselves. A life of hectic devotion to such disgraceful tenets of the modern era is an affront to the simplicity and beauty of the world, taking us farther away from the true goals that should pervade our lives. We should rather follow the example of the woodland spring ephemerals. Though diminutive in stature, with some barely able to rear their heads above the leaf litter, they freely share their gifts to all with an air of unpretending humility. When we finally have sense enough to see that this is as high a purpose as one need to strive to attain, we shall with ease command a different sort of success, attracting a steady following of those reverencing kind and radiant virtues, as a hidden flower has its loyal pollinators. There’s meaning and wealth in everything, regardless of position or stature. While those hidden among the detritus of the forest floor will be seen and respected only by a portion of the population, they will reside solely among the best company, having had unworthy visitors winnowed by the grate of the forest.

Find Your Eternity in Each Moment

Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life? We are determined to be starved before we are hungry. Men say a stitch in time saves nine, and so they take a thousand stitches today to save nine tomorrow. As for work, we haven’t any of consequence. –Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau was a man who valued time. Not in the monetary sense, as we are apt to envision today by the adage of “time is money,” but rather viewed it in broader, more cosmological terms, equating it with the eternal and divine. “Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in,” he says in Walden. “I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains.” Time is the gateway, the buffer, to the underlying force that imbues life with meaning and purpose. Squandering time as but a means to accumulate wealth, as Thoreau viewed it, was an act as profane as despoiling a church. How can we foster a relationship with the divine when we devote a majority of our time tirelessly working to accumulate possessions which will “moth and rust?” Our restless nature, devoted to toiling day in and day out for a “pecuniary reward” with the added benefit of keeping us busy and out of trouble, couldn’t be more base and uneducated. This misdirected work ethic doesn’t arise so much from greed as that “our vision does not penetrate the surface of things.” We view time, like the water in Thoreau’s metaphorical stream, as a commodity to be traded and sold, and not as the holy water that it truly is. Thoreau wetted his fingers in the current to obtain his victuals and other “necessaries of life,” but certainly didn’t immerse and drown himself in it as most of us commonly do today. A couple dabs a week was sufficient to sustain him. He sought focus on more important matters.

He understood moderation and sobriety. Instead of copiously imbibing in mostly fruitless work until he was too fatigued to accomplish anything of personal value, he substituted it for leisure and endeavors closer to the heart which no quantity of money could measure up to. He noted that most are “occupied with factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors” to the point where one has “no time to be anything but a machine” insomuch that the “finer fruits cannot be plucked.” The route that Thoreau pursued was one devoted to seeking out the mystifying and inspirational qualities of Nature, recording his unique sights and thoughts in poetry and prose. This was his divine life. To others it’s something else, just as personal and individualistic. We can’t aspire to this “higher and more ethereal life” without shifting our perception and giving up what society has solidified as bedrock. We must burrow beneath or soar above it. By living simply and attuned to the natural world Thoreau discovered that our main focus should be placed on the intangible. New experiences and opportunities are the “marrow of life.” Toys and technological gadgets which increasingly provide our main sources of extracurricular entertainment distract us by placing our time into purely external vectors that yield no dividend. Even the highest or most refined strain of materialism can’t replicate or supersede the benefits of an inherently humble, natural life. “The true harvest of my daily life is somewhat as intangible and indescribable as the tints of morning or evening,” Thoreau rapturously mused. “It is a little star-dust caught, a segment of the rainbow which I have clutched.” The relentless pursuit of wealth clouds the eyes, robbing us of the beauty and simplicity of nature. The “commercial spirit” which was the gospel and ruling force of Thoreau’s day and still animates and drives us at present, leads to an ingrained belief that commerce surmounts all else; without which the world would stagnate and collapse. Thoreau loathed this was of narrow way of thinking, ultimately upending it in his Harvard commencement speech in which he defiantly stated: “Let men, true to their natures, cultivate the moral affections, lead manly and independent lives; let them make riches the means and not the end of existence, and we shall hear no more of the commercial spirit. The sea will not stagnate, the earth will be as green as ever, and the air as pure. This curious world which we inhabit is more wonderful than convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used.”

Similarly, Thoreau was appalled to see how easily his contemporaries could be bought “off from their present pursuits” by “a little money or fame.” Chasing the almighty dollar over personal passions, he reasoned, cheated men from situations that were much more profitable to individual growth and understanding the larger, universal picture of existence. “To have done anything by which you earned money merely is to have been truly idle or worse.” Thoreau excelled at turning things upside down, making someone revisit a situation from a fresh angle or vantage point to see that there exists more than one way of thinking or interpretation. The accustomed standard of success rests upon following a set and tried formula. Plug in variables into the equation and take out a known logarithmic return. It works. Thoreau didn’t devise some entirely new scheme to circumvent this process, but instead, as he was rather fond of doing, simplified the equation to suit his particular tastes. We can best see his razor logic at work in this passage: "Not long since, a strolling Indian went to sell baskets at the house of a well-known lawyer in my neighborhood. 'Do you wish to buy any baskets?' he asked. 'No, we do not want any,' was the reply. 'What!' exclaimed the Indian as he went out the gate, 'do you mean to starve us?' Having seen his industrious white neighbors so well off — that the lawyer had only to weave arguments, and, by some magic, wealth and standing followed — he had said to himself: I will go into business; I will weave baskets; it is a thing which I can do. Thinking that when he had made the baskets he would have done his part, and then it would be the white man's to buy them. He had not discovered that it was necessary for him to make it worth the other's while to buy them, or at least make him think that it was so, or to make something else which it would be worth his while to buy. I too had woven a kind of basket of a delicate texture, but I had not made it worth any one's while to buy them. Yet not the less, in my case, did I think it worth my while to weave them, and instead of studying how to make it worth men's while to buy my baskets, I studied rather how to avoid the necessity of selling them. The life which men praise and regard as successful is but one kind. Why should we exaggerate any one kind at the expense of the others?" The ideas developed and touted by Thoreau and other Transcendentalists have often been described as too quixotic and impractical, that idealism can’t be a firm substitute for the realities of a harsh world. While some are indeed whimsical, crafted for purposes of morale and inspiration, a significant portion are practical to integrate into our daily routine. Thoreau wasn’t a man who preached hollow ideals; instead he staunchly embraced the words he uttered and demonstrated them to be true through experience, evinced by his experiment at Walden Pond. During his two year stay in the woods he conclusively proved that it was possible to throw off the yoke of society and still live a rich and meaningful life following one’s particular bent. The hard part was not getting away, but altering thought processes to ensure the allure of “civilized life” wouldn’t, like the sirens’ call, draw one towards the rocks. He was convinced “that to maintain one’s self on this earth is not a hardship but a pastime, if we will live simply and wisely.”

Terrariums

A terrarium is a world within itself, a tiny ecosystem capable of surviving almost entirely without human assistance. Add plants to a glass enclosure, sprinkle in a bit of soil and water, and ensure the system receives adequate sunlight, and a self-regulating system emerges. Creating one and watching it thrive bottled up amidst a harsh artificial human environment is a rewarding experience that provides a greater appreciation of the fortitude of nature. Adding a terrarium to the home or work space can help brighten up the surroundings in a natural and low-cost way that supersedes cut floral arrangements and prosaic static wall paintings. These elegant systems are living artwork, as it were, and continually morph before your eyes into a novel and inspiring mural of unique form and color. Terrariums are relatively easy to construct and require only a handful of basic supplies. To start out you’ll need a glass container (with or without a lid depending on whether you want an open of closed terrarium), medium sized river rocks (1-1.5 inches in length), coarse sand, and rich soil. The glass containers can typically be found at larger craft stores. Michaels and Hobby Lobby have a wide selection at low cost. It’s important to include three substrate layers when building a terrarium in order for it to remain healthy. I add river stones to the bottom, sand on top of that, and finally soil above the sand. Thickness wise you’ll have to gauge for yourself depending on the size of the container. I use a ratio of 2:1:3—two parts stone, one part sand, and for the largest addition, 3 parts soil. Unlike potted plants, a terrarium lacks drainage holes in the bottom of the container. Excess moisture will cause a whole slew of problems, especially if it has a lid. Watering is therefore a delicate task. The jumbled rocks on the bottom serve to help mitigate the inclusion of extra water by acting as a reservoir. Rocks of medium size work best because the spaces among them hold a fair amount of water and allow you to see exactly how damp the system is. The sand serves as a buffer between the two other layers and helps facilitate drainage. When it comes to choosing plants, there’s an extremely wide variety that can be grown successfully in a terrarium. Traditionalists tend to use small and slow growing species for closed terrariums and succulents or other plants that do well with minimal moisture for open ones. As long as the plants don’t grow excessively tall you can essentially include anything. I personally enjoy incorporating native flowering species into the mix, though they do frequently require a bit of effort to maintain.

If you’re after a stable, long-term terrarium, I would suggest sticking primarily to ferns, mosses, and other non-flowering plants. On the other hand, if you desire something more visually striking, and can handle a system that is relatively short-lived, an optimal addition would be spring ephemeral wildflowers. Violets, hepatica, red columbine, spring beauty, rue anemone, and trailing arbutus are among the multitude of small to medium sized ephemerals that can survive the rigors of confinement in a container. They should be added in the early spring just as the foliage begins to appear. Plants will remain in flower for a month at most, after which they should be taken out. They can be replanted in an outdoor garden until the following spring. Ephemerals can make do in a closed system in the beginning, but as the plants prepare to flower they will often exceed the height of the lid and it must be removed. Spring ephemerals can sometimes be bought at nurseries, but more often than not, they will be difficult to track down. Seeds can be purchased online for harder to find varieties. Of course, plants can also be collected in the wild, but this should only be undertaken if they’re in abundance or are threatened with imminent destruction. Once your chosen plants have been placed inside and a layer of soil tightly packed around the bases to make everything level, it’s time to add the final touches. For a lush and verdant look, as well as to keep the top layers of soil and roots sufficiently damp, it’s important to use moss as a covering for bare soil. What grass is to lawns, moss is to terrariums. Any type will work. A thick layer is probably best, as it lends a feeling of fecundity and age to the miniature ecosystem. Moss is also useful for indicating whether the system is properly hydrated. It should always be slightly damp to the touch. A closed terrarium is a microcosm of earth. The glass dome traps incoming solar radiation the same way our atmosphere does, producing a greenhouse effect. As the system warms, plants gradually draw water from the soil and rocky reservoir, transpiring it into the air above where it condenses on the glass, and either drips or slides back down the walls to continue the cycle. A properly constructed terrarium will require only the occasional maintenance.

|