Indian Brook Falls

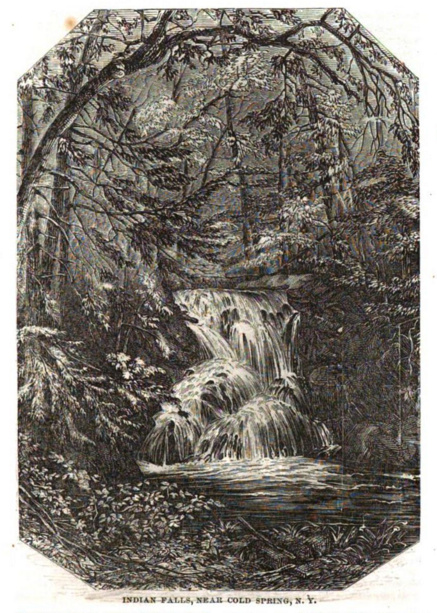

At the base of a deep and secluded ravine in the craggy confines of Putnam County, where the Hudson Highlands form an indomitable rolling wall of granite that makes even a short trip seem like a wild expedition, a small brook glides among jumbled boulders and the decaying trunks of hemlocks on its way to the Hudson River. About half a mile north of its terminus with the river, a sublimely beautiful 25 foot waterfall enlivens the tranquil, low-light surroundings. Indian Brook Falls has attracted countless visitors over the years, many of which, after glimpsing the wild grandeur of the spot, have been inspired to record the remarkable scene through paintings, verse, and prose (and now photography). Now residing on parkland, the falls are a protected treasure that will continue to offer its peaceful respite to all that require a momentary escape from the bustle of everyday life.

Flowing into a marshy cove of the Hudson, known as Constitution Marsh, the area surrounding the outlet of Indian Brook was occupied for thousands of years by Native Americans, who had a minor settlement in the vicinity. Waterfalls were sacred places to most native peoples, believing these spots were the abodes of spirits. It is therefore unquestionable that these Wappinger Indians, a subtribe of the more encompassing Lenape, regularly journeyed to the falls to pray and conduct other religious ceremonies.

The falls were once simply known as "Indian Falls," but the name was later changed during the 20th Century to "Indian Brook Falls," probably to help distinguish it from the myriads of others bearing identical names across the country.

Throughout the 1800's, numerous descriptions of the waterfall and associated treks out to it were published in both books and magazines. These writings reached a zenith during the Romantic era, a period in which emphasis was placed on aesthetic experiences derived most notably from the raw and sublime forces of nature. The writings are prolifically descriptive and vivid, eliciting the same level emotion that a mesmerizing photograph today provides. High profile writer-adventurers, such as Nathaniel Parker Willis and Benson J. Lossing, were among those that helped catapult the site to fame.

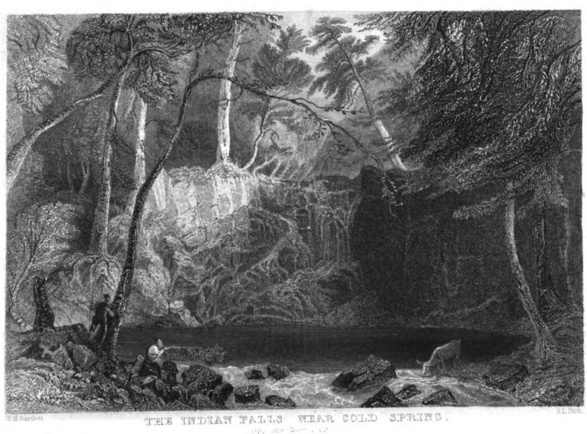

The noted essayist and author, Nathaniel Parker Willis, provides a singular description of the falls in his classic book, American Scenery, published in 1840. In his opening lines he calls Indian Brook Falls "a delicious bit of nature... possessing a refinement and an elegance in its wildness which would almost give one the idea that it was an object of beauty in some royal park." Further in his narrative, he documents an excursion out to the falls with a group of local residents aboard a wagon fashioned in the old Dutch style. To view the waterfall required travel on a rugged, and as he would later discover, dangerous road. The road was "in some places, scarce fit for a bridle-path," and so clogged with imposing rocks "which we believed passable when we had surged over [them]—not before." Eventually, a wide and level section of the road appeared; the driver then became “ambitious" enough to push the horses into a gallop, but being "ill-matched" in strength they jostled the fragile wagon in such a way as to detach several important features that sent the passengers flying to the floor. The mayhem was put to an end at a sharp turn in the road where the uncontrollable horses "unable to turn, had leaped a low stone wall." After salvaging one unbroken champagne bottle from "the wreck," the mostly uninjured party continued to the falls on foot and enjoyed a pleasant afternoon there.

Despite the unpleasantness of the journey before modern improvements made access easier, a visit to the falls was consistently undertaken by crowds of people in all temperaments and levels of physical ability. Though the Hudson Valley held many additional spots of attractive natural splendor, Indian Brook was described to contain "the most beautiful of its scenery." Aside from the pleasing cascade, the uncontaminated wildness of the spot drew crowds hoping to glimpse a portion of the country that hadn't yet been altered by progress and still held the same untouched features that its native inhabitants once viewed. Elsewhere in the valley, logging and farming had tamed the land and turned much of it into a quaint pastoral setting. But in the rugged Highlands, the land, as an article writer for The Ladies' Repository described, was "self-defended by the integrity of nature" with its "palisadoed inaccessibility," and that the "hardiest engineer will know it is not 'worth while' to delve amidst these rocks." Here, people could come and romanticize about Indians and days of old in the proper setting, without having to travel to equally pristine settings out West or to the northern extremes of the state, like the Adirondacks.

Despite the unpleasantness of the journey before modern improvements made access easier, a visit to the falls was consistently undertaken by crowds of people in all temperaments and levels of physical ability. Though the Hudson Valley held many additional spots of attractive natural splendor, Indian Brook was described to contain "the most beautiful of its scenery." Aside from the pleasing cascade, the uncontaminated wildness of the spot drew crowds hoping to glimpse a portion of the country that hadn't yet been altered by progress and still held the same untouched features that its native inhabitants once viewed. Elsewhere in the valley, logging and farming had tamed the land and turned much of it into a quaint pastoral setting. But in the rugged Highlands, the land, as an article writer for The Ladies' Repository described, was "self-defended by the integrity of nature" with its "palisadoed inaccessibility," and that the "hardiest engineer will know it is not 'worth while' to delve amidst these rocks." Here, people could come and romanticize about Indians and days of old in the proper setting, without having to travel to equally pristine settings out West or to the northern extremes of the state, like the Adirondacks.

The area not surprisingly became "a favorite subject with artists." Numerous paintings and engravings exist from the 19th Century that render the locale in near perfect likeness, and served as a simple photograph would do today in a newspaper or feature article. Others, however, show more free rein by the artist, boasting exaggerated features that are in tune with the particular inclinations and feelings of the era. The various depictions are useful for peering into the minds of the past and being able to witness firsthand the impressions the location made on these first intrepid nature seekers.

Another valued feature of the spot was its ability to act as a panacea, or restorative, to both the mind and body. "Tourists are always in raptures with the Falls," the editor of Dollar Monthly Magazine wrote in 1864, "because the sound of the moving waters is pleasing to the senses, soothing those who have tender nerves, and creating a feeling of delicious happiness." In a similar vein, another advocate of the potential healing powers of Indian Brook rapturously exulted, "May the heart, the spirits, the soul be here refreshed and refined!" Clearly, just as the Indians before them, the early residents of the Hudson Valley viewed powerful sites like these in a sacred manner. The unspoiled surroundings resembled to them an Eden, and they appropriated their time there accordingly. At the base of the plunging falls is a deep, expansive basin filled with transparent water and edged with a soft gravelly bottom, appropriately named the Musidora Pool (translated to "Gift of the Muses"), which according to Willis, "Nature has formed it for a bath." One has to wonder how many visitors over the years have cleansed themselves in the crisp water of the pool, similarly to the ablutions of a baptismal font.

While during the day Indian Brook was the epitome of Hudson Valley beauty, as night overtook the already blackened ravine, the surroundings rapidly put on a gloomy demeanor as darkness and a diverse assemblage of shadows proliferated in the steep sloped and narrow chasm. This now lonely and increasingly fearful spot became the perfect haunt for spirits. A mixture of both reverence and apprehension undoubtedly swirled around the minds of those on their way to Cold Spring or Garrison as they crossed the tiny stone bridge that spanned the brook only a short distance downstream of the falls.

While during the day Indian Brook was the epitome of Hudson Valley beauty, as night overtook the already blackened ravine, the surroundings rapidly put on a gloomy demeanor as darkness and a diverse assemblage of shadows proliferated in the steep sloped and narrow chasm. This now lonely and increasingly fearful spot became the perfect haunt for spirits. A mixture of both reverence and apprehension undoubtedly swirled around the minds of those on their way to Cold Spring or Garrison as they crossed the tiny stone bridge that spanned the brook only a short distance downstream of the falls.

Legends and ghost stories held in distant memory, were quickly dug out from the dusty recesses of the mind and recalled in perfect detail. Unable to think of anything else, these thoughts took on a life of their own. Was the sound echoing out of the inky darkness upstream the melancholy weeping from the ghost of a jilted Indian maiden who took her own life rather than deal with the loss of her lover, or was it simply the potent roar of the falls obscured and dwindled by the wind rushing through the valley? Was the trembling figure crouched amid the bushes, the protective spirit of a dog still doing his master's bidding even in death, or was it merely a prostrate log, given an animal resemblance by the pale luster emanating from the full moon overhead on a clear late-fall evening?

Legends and ghost stories held in distant memory, were quickly dug out from the dusty recesses of the mind and recalled in perfect detail. Unable to think of anything else, these thoughts took on a life of their own. Was the sound echoing out of the inky darkness upstream the melancholy weeping from the ghost of a jilted Indian maiden who took her own life rather than deal with the loss of her lover, or was it simply the potent roar of the falls obscured and dwindled by the wind rushing through the valley? Was the trembling figure crouched amid the bushes, the protective spirit of a dog still doing his master's bidding even in death, or was it merely a prostrate log, given an animal resemblance by the pale luster emanating from the full moon overhead on a clear late-fall evening?

The latter ghost was said to be the mastiff of Captain Kidd. A somewhat outrageous legend claims that Kidd burnt his ship in the vicinity around West Point to avoid capture by authorities. And by rowboat, he brought a portion of his secreted treasure to the mouth of Indian Brook where he promptly buried it. Before covering it up, he killed his dog and placed the body atop the pile of gold, so that the creature would guard it until his return. He never did make it back, though, having later been seized in Boston, transported to England for trial, and finally hung for piracy in 1701.

As crazy as it might seem to have the infamous Captain Kidd sailing through the Hudson Highlands, he did have roots in the area. He made his home in New York City and had legal privateering expeditions financed by his associate Robert Livingston. It was said that he and his crew were sailing for Livingston Manor in the upper Hudson Valley the night the ship was lost.

Numerous other legends abound as to the supposed location of his loot. Some say his ship sunk at the base of Dunderberg Mountain across from Peekskill and most of his gold still lies beneath the waters of the Hudson. Others attest it's hidden on the precipitous slopes of Crow's Nest Mountain behind a massive, unwieldy boulder called "Kidd's Plug Rock." And an even more unlikely tale tells of him transporting it west to the Shawangunk Mountains, where it was hidden in a remote cave among impenetrable pitch pine barrens.

An 1880 editorial in the Putnam County Recorder claimed that "the dog's haunts are around the bridge that spans the chasm, just below the falls, sometimes being seen on one side, sometimes on the other." It further goes on to mention that one night as a carriage approached the haunted area at around "ten o'clock with six persons" aboard, a member of the party jokingly said, "'Now let us look for the dog.'" Almost immediately after uttering those fateful words a wild looking mastiff materialized alongside the wagon and began to make menacing gestures. The driver having a gun on his person, pulled it out and fired six shots into the beast. The bullets had absolutely no effect, and the phantom dog held his ground until the terrified group had quickly proceeded on their way.

Though the old bridge still stands and provides access for the curious visitor eager to view the stunning scenery surrounding Indian Brook Falls, a modern arch bridge now spans the rim of the ravine 200 feet above the murmuring brook and farther downstream than its predecessor, keeping heavy Route 9D traffic away from the scene. Since travelers at night no longer pass by for a possible encounter with the supernatural, the area has been given a greater degree of solitude than it has seen in a long while. The tranquility and unblemished wildness, so prized by those of an earlier era, remains intact and welcomes the wanderer with the same delights first witnessed by its aboriginal stewards.

Though the old bridge still stands and provides access for the curious visitor eager to view the stunning scenery surrounding Indian Brook Falls, a modern arch bridge now spans the rim of the ravine 200 feet above the murmuring brook and farther downstream than its predecessor, keeping heavy Route 9D traffic away from the scene. Since travelers at night no longer pass by for a possible encounter with the supernatural, the area has been given a greater degree of solitude than it has seen in a long while. The tranquility and unblemished wildness, so prized by those of an earlier era, remains intact and welcomes the wanderer with the same delights first witnessed by its aboriginal stewards.

***

"At every turn of the brook, from its springs to its union with the Hudson, a pleasant subject for the painter's pencil is presented. Just below the bridge, where the highway crosses, is one of the most charming of these 'bits.' There in the narrow ravine, over which the tree tops intertwine, huge rocks are piled, some of them covered with feathery fern, others with soft green mosses, and others as bare and angular as if just broken from some huge mass, and cast there by Titan hands." -Benson Lossing, 1866, The Hudson, from Wilderness to the Sea

"At every turn of the brook, from its springs to its union with the Hudson, a pleasant subject for the painter's pencil is presented. Just below the bridge, where the highway crosses, is one of the most charming of these 'bits.' There in the narrow ravine, over which the tree tops intertwine, huge rocks are piled, some of them covered with feathery fern, others with soft green mosses, and others as bare and angular as if just broken from some huge mass, and cast there by Titan hands." -Benson Lossing, 1866, The Hudson, from Wilderness to the Sea

***

Legend of “Indian Brook Falls”

Legend has it that during Henry Hudson's 1609 expedition, the Half Moon anchored one day near the mouth of Fishkill Creek. On a foray into the countryside, the crew stumbled upon clusters of wild grapes which they eagerly began collecting, hungry for anything other than a mouthful of stale sea rations. Intent upon the task at hand, they were unaware a group of Indians had arrived and surrounded them. Eventually, a crew member happened to notice something moving in the nearby bushes and walked over to investigate, at which time a volley of arrows were launched at the intruders. Having left a majority of their weapons back on the ship, there was little to be done except retreat. During the brief skirmish, the Dutchman Jacobus Van Horen was struck by an arrow and promptly captured. Assuming their compatriot was dead, the Europeans sailed on, never to return to so hostile a spot.

Jacobus was transported south and presented to the sachem of the tribe. Intrigued by this strange white man, the first he had ever seen, he instructed his people to properly care for the prisoner. Over time, Jacobus was able to gain their trust, and was incorporated into the tribe. Meanwhile, the sachem's daughter, Manteo, quickly become enamored with the Dutchman and eventually asked her father permission to marry him. He happily agreed to the request and a wedding was set for the following summer.

Over the following months Manteo and Jacobus would often meet at a secluded waterfall, sacred to her people, at the bottom of a deep and shaded ravine. Sitting beside the cascading waters that in little distance poured into a marshy cove of the Hudson, Manteo would muse with her lover about their upcoming nuptials and future together. Jacobus smiled and reciprocated the kind words, but inwardly he deeply missed his homeland and secretly prayed for deliverance.

One spring day his prayers were answered. While out on a hunting trip, the deafening report of a gun noisily echoed through the still woodlands. Jacobus in an instant dropped everything and ran towards the direction of the shot. He eventually came to the shores of the Hudson, and spotted only a few hundred yards away an anchored ship flying a Dutch flag. Jumping into the water without the least hesitation, he swiftly swam up to the vessel and was taken aboard. And from there he disappeared.

Manteo was heartbroken with this sudden departure, receiving not so much as a good-bye from the one she thought deeply loved her. Not long after, she too, disappeared. A few days later her body was discovered at the base of the waterfall she had spent so much pleasant time beside with Jacobus. Grieved beyond all consolation, it appeared she had taken her own life.